Re-Reading The Postmodern Condition

Most people think that the main point of Jean-Francois Lyotard’s The Postmodern Condition is about the “end of grand narratives.” Watch any YouTube video summarizing this work, and that’s the phrase you’ll find. That is not what he writes, at least not in the introduction where he uses something like this phrase. Here is what he actually says (as translated by Bennington and Massumi): “Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodern as incredulity toward metanarratives” (xxiv). The operative term is incredulity, which is not an end, it is a kind of skepticism. At most it is, as a later term in the same paragraph puts it, an “obsolescence.” By putting the emphasis on incredulity, Lyotard’s postmodern condition is about beliefs — what do we find credible and un-credible? Metanarrative-based societies ask us to believe in the legitimacy of the overriding narrative. This makes membership in these societies a matter of our disposition to the truths we are told.

If there is something new about “the postmodern condition,” it is the number and complexity of the messages that one must interact with continually. This complexity has to do with the sheer number of language games we have to deal with in an age where information is commoditized and flowing through multiple channels. The “self” is not “atomized” in this situation. It is a “nodal point” within “specific communication circuits.” It is a “post through which various kinds of messages pass” (15). Far from being atomized, we are tied in. Incredulity emerges as the inability to synthesize these messages into a unified story of what is happening around us. As everything becomes harder and harder to reconcile and synthesize, our unwillingness to believe in any metanarrative we are told rises. This incredulity, then, is an effect of the interacting systems that need the “self” to be a consumer and producer of information that keeps the “information economy” working. One of its primary effects is to make visible language games as games with their own internal rules that can be surfaced and discussed. This exposes the hierarchical relationships among different games as a game itself — a game of interacting games — and thus not beholden to any universal truth that would justify the hierarchy. But more on this later.

There is a second part of that sentence to point out. Metanarratives is deliberately plural. It is not the incredulity toward one particular metanarrative, but incredulity to the form itself. We must understand its form to understand what is becoming obsolete. It is not that the Enlightenment metanarrative of progress is obsolete (including any of its progress-based variations, especially Marxism or social-Darwinism). Modernity was solidified by a collusion between two quite different “language games”: science with narrative as metanarrative. That collusion is facing incredulity and becoming obsolete. How did that collusion work? That is the historical genealogy that Lyotard is delving into in The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge. Understanding this collusion is what I want to spend time understanding as I undertake what will probably be a long-term re-engagement with Lyotard.

……….

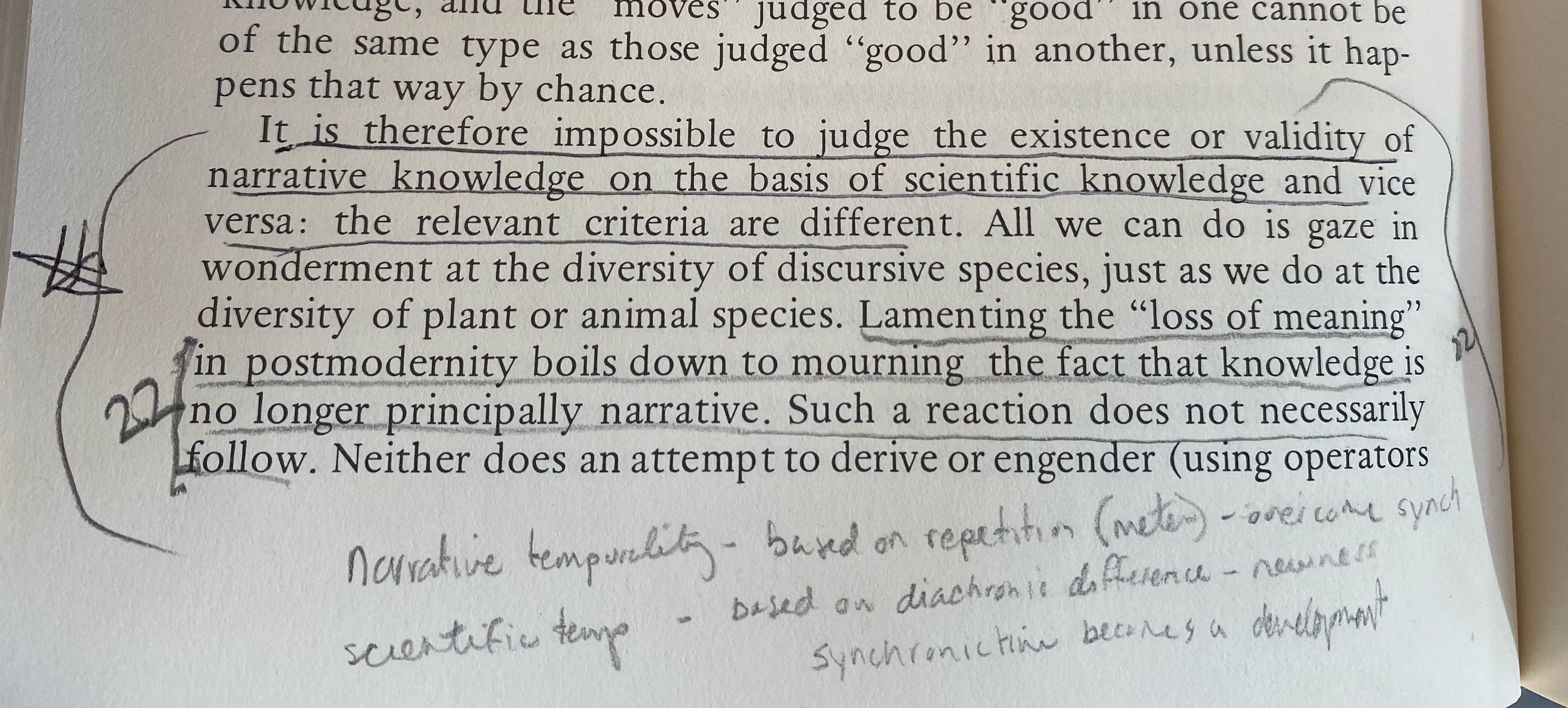

Side note: I’m going back to a copy of The Postmodern Condition that I’ve owned since 1993. As I go through it again, I’m finding different passages important compared to what I marked up when I first read it in the early-1990’s as an ardent, young, self-identified “post-structuralist.” To mark the different readings, I’m noting “22” (for 2022) where I make notes in the margins today.

……….

This meditation is going to start with a single paragraph — the one from the picture above:

It is therefore impossible to judge the existence or validity of narrative knowledge on the basis of scientific knowledge and vice versa: the relevant criteria are different. All we can do is gaze in wonderment at the diversity of discursive species, just as we do at the diversity of plant or animal species. Lamenting the “loss of meaning” in postmodernity boils down to mourning the fact that knowledge is no longer principally narrative. Such a reaction does not necessarily follow. Neither does an attempt to derive or engender (using operators like development) scientific knowledge from narrative knowledge, as if the former contained the latter in an embryonic state. (27)

While Lyotard does not use the term “incommensurability” here, this is exactly the dynamic he is describing. Incommensurability occurs when you try to reduce different things to being measurable by the same yardstick. Here, narrative and science are incommensurable with respect to how each of them define “knowledge.” I’m going to try to unpack this at some length in this meditation because I think that there is a profound understanding of nihilism packed away in this statement that I want to get my head around.

Science creates an alignment between “knowledge” and “truth” where truth is understood to be represented by statements that can be subject to “proof.” This implies an entire set of pragmatics that revolve around truth as the provability of statements: “a referent is that which is susceptible to proof and can be used as evidence in a debate” (24). Truth, in other words, is preconceived as anything that can be “proven” by peer-to-peer demonstration and repeatability. Copernicus demonstrated that the planets revolve around the sun, not vice versa. In making this statement, he was playing within a game of science where the objective is to make claims about a “referent” or “referents” (the sun and the planets) that can be shown to be true through arguments and experiments. If enough experiments accumulate showing that this situation can be repeatably proven, then the statement, “The planets revolve around the sun” is now considered true and is therefore “knowledge.”

This all seems rather obvious. But there are consequences that are important for our postmodern condition. One consequence is that the provable is subject to “falsification” — at some point an experiment can come along that throws a monkey wrench into the game. What we thought we knew may no longer be true. Thus within the game of science — the game where the only legitimate knowledge is an expression of provable truths — falsification is always hanging around. It plays a fundamental role within the language game of science.

But what does falsification do with the accumulated knowledge that came before it? It must cast the past as mistaken — we didn’t know the truth. What we thought we proved to ourselves was an illusion. Thus science always contains within it postmodernity’s sense of the “loss of meaning.” This loss of meaning, however, does not rise to the level of a social problem unless other conditions are present. Without another connection — what Lyotard will eventually introduce as “metanarratives” — the loss of meaning would simply remain internal to the specific science being practiced. Copernicus’ problems occurred not because he offered a falsification of previous sciences, but because that falsification connected with other narratives that justified a particular social order. But that is jumping ahead too far, too fast.

The second consequence is this: to be knowable, provable and falsifiable, “reality” must be stable and univocal — in short, it must be Platonic. Specifically, multiple truths about the same referent are not possible. This is what falsification means: “the same reference cannot supply a plurality of contradictory or inconsistent proofs” (24). There is, in other words, only one right answer. “God is not deceptive,” or as Einstein is supposed to have put it “God does not play dice with the universe.” If the planets are proven to revolve around the sun, the reverse cannot be true. Only one truth is possible and it will not likely change. If it does change, then there was a deeper truth about reality that we missed. This is what falsification means.

The third consequence of the scientific language game is this: falsification implies a specific experience of time as progress and development. For all its anxiety-producing “loss of meaning” moments, falsification is the engine that drives the will to truth. The scientist knows this is how the game is played. She dusts herself off and gets back in the game because this is how the game works — you keep trying to align knowledge with truth. The loss of meaning is absolutely essential to the dynamics of the game.

The fourth consequence of the scientific game is perhaps the most important for Lyotard and the postmodern condition: all forms of knowledge are measured by the scientific standard. Knowledge is attained by proving things to be true, or by falsifying what we thought we knew so as to inject new energy into the will to truth. It is not that other forms of knowledge are not conceivable. I know how to type. I know how to throw a baseball. I know how to drive my car to the store. The thing is, science either devalues these forms of knowledge as lesser — because they are not aligned with truth — or it tries to reduce this knowledge to scientific statements. How my fingers move intuitively across the keyboard can be understood through the provable mechanical and neurological processes of human physiology.

This has the effect of scientific language games wanting to separate themselves off from other games and devaluing those games as lesser forms of knowledge. Science stands “outside” of those games and judges them as inferior while putting them to the scientific test. Science, therefore, introduces a criteria of legitimacy that measures all other forms of discourse — art, ethics, and any kind of practical “know how” — as versions of itself. It provides the benchmark by which all other forms of knowledge are judged. While Lyotard doesn’t cite Nietzsche, we can see the ascetic ideal in action here. For example, my ability to throw a baseball from the outfield to home plate with precision is scientifically reducible to the physiological mechanics involved. This is the way that a physiologist would look at my ability to do this. This has the effect of devaluing my experience of being able to do this in order to get at its truth — the ascetic ideal in action. To have your back to the play so that you can catch a throw from an outfielder, quickly turn your body around and focus your attention on where the runner is and whether or not you have enough time to make the throw — then making the throw and having it land exactly where you want it at home plate in the catcher’s glove a split second before the runner gets there is an incomparable experience. To reduce it to scientific statements as its truth is to devalue the experience that this kind of know how affords.

In this case, the experience itself is its truth. No explanation is needed for that feeling to be true and powerful. The telling of the tale as narrative certainly reactivates the feeling and is valuable for that retelling — if only to myself. But science wants to find a truer truth hiding behind the scene itself and accessible only to the initiated. In the game of scientific discourse, my experience is lesser as a form of knowledge and also reducible to some other explanation hidden behind and within my experience.

In enumerating and elaborating on these consequences, I’m getting at Lyotard’s sentences in the paragraph I cited at the beginning: “All we can do is gaze in wonderment at the diversity of discursive species, just as we do at the diversity of plant or animal species. Lamenting the ‘loss of meaning’ in postmodernity boils down to mourning the fact that knowledge is no longer principally narrative. Such a reaction does not necessarily follow.” What is the “reaction [that] does not necessarily follow?” One is relativism. To see the differences among language games as a wonderful diversity is not only to give into a nihilistic relativism: it is to cut off the analysis of how language games are “agonistic” between themselves — they are in conflict. Sometimes this conflict is relatively benign. Sometimes this conflict leads to collusion — as with science and metanarratives. Other times the conflict is openly hostile. I will have to return to this later.

Another reaction that is not automatically justified is a broad-based sense of the “loss of meaning.” This is the flip side of relativism. Lyotard thinks that the loss of meaning results from the rise of scientific discourse as the measure of all knowledge. This is an important point, and I want to spend some time dwelling on it. When other kinds of knowledge are devalued in the name of science — particularly the kinds of knowledge that give one a sense of belonging and accomplishment (which is the heart of narrative knowledge), it is easy to feel a loss of meaning. Does my experience of knowing how to make that complex set of moves to throw out the runner at home not count as meaningful? Was my experience simply hiding a truer truth? Must I reduce my experience to physiological and psychological descriptions to get at its true meaning?

Postmodernity, therefore, is not a recent phenomenon as the “loss of meaning.” It was already a condition of modernity when it elevated science to the measure of all knowledge. This elevation required the demotion of other forms of knowledge, especially narrative. Once science becomes the primary language game that is productive of knowledge and truth, it gains control of meaning. Other kinds of meaning — storytelling, painting, poetry, et cetera — lose their status because their version of meaning-knowledge-truth are not scientific. Meaning is untethered from truth. They can still have value, but this value is lesser than science. This loss of status is the loss of meaning that is inherent in modernity. We don’t have to “wait” for postmodernity for this sense of loss.

Another example is in order. This is my example, not Lyotard’s. Let’s take the creation story as told in Genesis. It is clearly a narrative form of knowledge that seeks to provide meaning about humanity’s relationship to a created cosmos. I’m not going to go into a detailed reading of Genesis — I’m not qualified for this right now. It clearly had value for many societies for thousands of years as did similar stories of creation. Today we call these “myths” — a mostly scientific term that consigns narrative knowledge like this to more “primitive cultures.” But that consignment must come with a profound sense of loss. To replace it with “natural selection” and the impersonal forces of evolution sucks the life out of these narratives. Yes, Genesis still has “meaning,” but that meaning is now merely a historical curiosity about how pre-modern cultures express themselves.

The attempt to assert “Intelligent Design” in the American classroom emerges from a “loss of meaning.” As such, it is an attempt to restore the power of narrative to an equal alongside science — but only by changing the terms on which creation stories can be said to have meaning. It is an enactment of exactly what Lyotard argued about postmodernity — the “loss of meaning” as the devaluation of narrative in favor of knowledge-as-provable-truth. Intelligent Design gives up the incommensurability of Genesis because the narrative is asserted as true on scientific terms. For some, it requires mind-boggling levels of mental acrobatics to see the story as literally true despite the fossil record (which can only appear as just another version of the serpent’s apple.) For others it is more plausibly a symbolic truth where the creation story is simply a literary rendering of the Big Bang for cultures that didn’t have our scientific concepts and precision yet worked out. In either case, incommensurability is elided in favor of legitimizing Genesis in scientific terms — its meaning is reducible to its knowable truth and not to the sense of belonging it provides to the cultures in which it emerged.

This postmodern “loss of meaning” is not a late development. Postmodernity does not come after modernity. As a sense of loss, it is embedded in modernity at its inception. As science emerged as the measure of all knowledge, other forms of knowledge were necessarily devalued thus leading to a sense of loss at the beginning of modernity. As such, the sense of loss is a dynamic embedded in modernity, and it will Eternally Recur. How else could Nietzsche lament the Death of God as a nihilistic loss of meaning in the late nineteenth century, well before any historical designation of a postmodern condition could have been possible?

___________

While science holds itself out as the benchmark for all other forms of knowledge, it is incapable of justifying and legitimizing that benchmark on a society-wide basis using its own internal logic. It needs another form of knowledge — another language game — to do that work for it. This is where The Postmodern Condition really gets interesting. Science has to rely on narrative for its legitimacy because science can’t tell stories about how it is the hero of humankind — only narratives can do that. So even as science denigrates narrative (because it is not “true” like scientific truths), it has to rely on narrative for its social position as the privileged form of knowledge. This means that there has to be an alliance between two incommensurable language games. We can describe this alliance as the “modern condition.” In the process, “narrative” becomes “metanarrative” because it rises above all the forms of scientific discourse to provide their justification and legitimacy to the broader culture.

Let’s take the Enlightenment for clarification. The Enlightenment is not just an historical time period in the Western world — roughly beginning in the seventeenth century and proceeding through to the early nineteenth century. It is purported to be the moment in history where humankind (at least in the West) discovered that scientific knowledge was the driver of human progress. That last sentence alone contains the alliance between science and narrative. “Human progress” is the metanarrative that justifies how much time, effort, money and power flows into scientific endeavors. For example, Great Britain spent a great deal of money improving its road system in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The techniques developed by engineers like Telford and McAdam (from whom we get the term “tarmac” for “tar macadam”) were increasingly scientific in their approach — taking into account how materials could be combined to make better roads that would withstand increasing amounts of traffic. But “McAdamized roads” (to use the term at the time) cannot justify themselves. All that the language game of “engineering” can do is show you how to build good roads. Engineering by itself can’t tell you why a society needs good roads. It needs a metanarrative of “progress and improvement” in order to garner the kind of legitimacy necessary to flow capital into these efforts — which happened largely through new institutional inventions like the “turnpike trust system” of the eighteenth century.

Of course, the alliance between science and metanarrative is tenuous. If scientific knowledge is presumed to be the ur-knowledge, then the metanarratives that provide its sociopolitical legitimacy are susceptible to scientific critique. It is important to remember that metanarratives are still narratives, which means from the perspective of science, they are inferior forms of knowledge (literature, storytelling, myths) that are susceptible to scientific critique. Thus metanarratives can be exposed as myths which is what science thought narrative knowledge always has been.

There is also another problem. Scientific knowledge, in seeking its legitimacy from narrative, must take a hard look at itself. When forced to justify itself, science cannot rely on itself. It must tell its story in terms of the progress of humankind. This is a very unscientific “presupposition” (38) that it must appeal to. And thus we have exposed the inherent problem in the alliance between metanarrative and science: in seeking to legitimate itself, it has recourse to metanarratives that are founded on “presuppositions” about human emancipation and progress, which themselves are not scientific presuppositions as they cannot be proven. The presupposition must remain a motivating assumption that gives meaning to the Enlightenment endeavor. Thus his statement that “the seeds of ‘delegitimization’ and nihilism that were inherent in the grand narratives of the nineteenth century” (38). Again, the postmodern condition is embedded in the modern condition as the tenuous relationship between science and the grand narratives it requires to hold onto its pride of place in modern societies.

Once science needs to justify itself using a very unscientific language game, science itself becomes exposed and loses its direction:

The “crisis” of scientific knowledge, signs of which have been accumulating since the end of the nineteenth century, is not born of a chance proliferation of sciences, itself an effect of progress in technology and the expansion of capitalism. It represents, rather, an internal erosion of the legitimacy principle of knowledge. (39)

This “internal erosion” is the emergent incredulity over any metanarrative of progress. It is “internal” in the sense that it is internal to the bargain that modernity made between two incommensurable forms of knowledge. This was not exactly a match made in heaven. This tenuous relationship between metanarrative and scientific knowledge makes “the postmodern condition” a strong possibility embedded in “the modern condition” from the very beginning. This is the paradoxical nature of the postmodern condition that must be understood, and it is the heart of the story Lyotard tells.

_____________

The dynamic that this introduces is important to understand: “What we have here is a process of deligitimation fueled by the demand for legitimation itself” (39). By making science repeatedly justify itself using the language of metanarratives, this very repetition increasingly exposes the problematic bargain between science and narrative. The bargain based on the metanarrative of human progress becomes less and less credible. Perhaps the most important effect of this, according to Lyotard’s telling of the tale, is the exposure of “an idea of perspective that is not far removed, at least in this respect, from the idea of language games” (39). In other words, language games rises to the level of our experience as we begin to see, through the demand that science justify itself in a foreign language game, the whole social field as an interaction of games.

This bears repeating and summarizing: One of the manifestations of this “internal erosion” is the exposure of this bargain between science and metanarrative as language games. How we speak with each other, how we know what we think we know, what counts as truth: these are all exposed as open questions, and the “presupposition” of human progress is exposed as a presupposition that must be questioned and thus become subject to criticism and choice. So, it is not just that language games are a theoretical device for Lyotard to highlight the features of the modern and postmodern conditions. Lyotard presents language games as what we experience when we realize that the legitimacy bargain between science and metanarratives is obsolete. The effect is “delegitimation,” and “the postmodern condition” can be seen as a conscious state of delegitimation shared across the sociopolitical landscape. Thus we arrive at “incredulity toward metanarratives” as the consciousness of sociopolitical legitimation as itself a game.

If this is not clear already, we should not be tempted to see the incredulity toward metanarratives and the delegitimation this implies as some kind of awakening to the human condition. This would mean holding onto the modern metanarrative of progress and improvement: either “the human spirit” is realizing itself as it comes to a self-awareness of the truth of its human condition, or human emancipation is being achieved as this incredulity is yet another expression of the Aufklarung metanarrative. Something else is happening that Lyotard understands as the realignment and transformation of language games. The second half of The Postmodern Condition digs into what happened to transform the “internal erosion” cited above into the postmodern condition.

To summarize and oversimplify the new (i.e., postmodern) condition: the pursuit of knowledge is no longer equivalent to the pursuit of truth; the pursuit of knowledge is measured by its ability to produce wealth and accumulate power. This is driving the obsolescence of modern metanarratives, and it is intimately related to the postmodern alliance of information technology and the accumulation of power. This alliance is brought about by the replacement of knowledge as stable, provable truth with knowledge as “performativity — that is, the best possible input/output equation” (46).

But it is probable that these narratives are no longer the principal driving force behind interest in acquiring knowledge. If the motivation is power, then this aspect of classical dialectics [i.e., university instruction] ceases to be relevant. The question (overt or implied) now asked by the professionalist student, the State, or institutions of higher education is no longer “Is it true?” but “What use is it?” (51)

The latter question manifests itself in other questions of value absolutely recognizable today: “Is it salable?” and “Is it efficient?” If there is a metanarrative here, it is not about emancipation or the fulfillment of humanity. It is about the accumulation of wealth as a means to power. Of course, this can be cloaked in either of the two modern metanarratives, but that is optional and hollow at best. It provides a thin veneer of moral cover. But if, as in the case of Donald Trump, moral scruples get in the way, then the veneer can be abandoned so that naked pursuit of power can stand on its own as a moral value of absolute power and the ability to command wealth. Such a figure as Trump strips off the last vestiges of the cloak of metanarratives. He is a figure without a moral history — without a developmental trajectory. He is pure wealth generation — the definition of American success. It is no coincidence that his willingness to play fast and loose with the truth is part of the game he plays. All that matters is his ability to generate his own success and power for himself over and over again, even after multiple bankruptcies. Whatever “alternative facts” are required to win is fair in this game. It does no good for the Left to criticize Trump on the Left’s modernist terms — he’s against democracy, he lacks integrity, he denigrates scientific knowledge, he makes up his own alternative facts. For those who believe in the postmodern games of power and wealth accumulation as the ultimate moral value, Trump is playing the game masterfully, and all of these things the Left hates about him — the object of their ressentiment — are positive and valuable tricks of the trade.

In the worldview of Silicon Valley, this metanarrative cloak is worn as hollow statements about being “mission driven.” This is not a nostalgia for metanarratives but the absorption of them into wealth creation. It makes us feel good about the naked pursuit of “multiples of EBITDA” and “ownership stakes” while we claim to be making positive change in the world. It’s a corporate communications function. But the engine behind the scenes is the venture-capital-fueled creation of wealth as the game itself. Venture capital and all its variations (“seed capital,” “friends and family capital,” “private equity,” “convertible debt,” et cetera) are only always about turning money into more money. “Exit strategies” is the euphemism that belies the fact that there is no metanarrative of human emancipation at stake. All that is at stake is getting out with much, much more money than you went in with. This is itself the rule of the language game. On occasion we might denigrate this ethic — as in the HBO series — but it doesn’t hold for very long. Companies exist not to improve our lives but to create wealth. In the process, they become commodities themselves. They are bought and sold as products and are not simply the creators of products.

Lyotard talks about this dynamic in terms of how “research funds” are allocated, but he is writing in the late 1970’s before venture capital becomes a thing:

Research funds are allocated by States, corporations, and nationalized companies in accordance with this logic of power growth. Research sectors that are unable to argue that they contribute even indirectly to the optimization of the system’s performance are abandoned by the flow of capital and doomed to senescence. (47)

How is this not a prediction of venture capital as the acceleration, intensification and further privatizing of this demand for wealth creation as the yardstick for measuring the value of knowledge?

Legitimation in this game is completely transformed. Modernity’s tenuous bargain between narrative and science is made obsolete because wealth creation becomes its own self-legitimating system. Wealth creation, in other words, replaces modernity’s language games of legitimacy (based on the pursuit of knowledge as the pursuit of truth) with a single game: the pursuit of power as the control of information and the infinite production of wealth. Such a system does not need metanarratives as its legitimating language game. Here it makes sense for me to return to the problem of the obsolescence of metanarratives and its relationship to incredulity.

As I mentioned earlier, incredulity is not an awakening of humanity to its (postmodern, modern, or eternal) condition. Incredulity of this kind does not create obsolescence as if, to borrow a phrase from Kant, humanity is now “emerging from its self-imposed immaturity.” This is not a tale of Aufklarung. Instead, obsolescence is a consequence of the internal revaluation of scientific language games and how those games are being absorbed into the self-legitimating game of power. Incredulity toward metanarratives is an effect of obsolescence and not its cause. Metanarratives are unhelpful in a new game of legitimation that sees constant improvement in “performantivity” (which is the ability to create wealth and power) as its only goal. We may still have recourse to narratives of “human emancipation” and “the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake” from time to time, but these are now either in the service of corporate mission statements as cloaks for its own accumulation of power, or they are lamentations from the Left that the game has moved on.

If incredulity can be described as arising from a new form of legitimacy, there is another dynamic at play that is driving incredulity: a change in the very nature of truth and what it means to know something. This change is twofold. First, the emergence of quantum physics, fractal geometry and other movements within science have removed our ability to believe in a stable referent that can be reduced to a repeatable proof. Truth is no longer Platonic in the sense of being eternal, stable, and able to be proven repeatedly. It is one thing if this death of provable, stable truth occurs outside of science; it is quite another if this is happening in the language game that has, for several centuries, held itself out as the exemplar of truth. It no longer has any leg to stand on to hold itself out as higher and better than other language games when it comes to creating knowledge. All it has done is shown that truth and reality aren’t what we thought they were. Science’s essential ability to falsify its proofs has turned into the falsification of its very assumptions about the nature of reality and whether anything can be proven definitively.

Second, if truth is no longer as Plato thought it was, what it means to scientifically know something changes dramatically. From knowledge-as-certainty, we arrive at knowledge-as-probablity. Specifically, what it means to scientifically know something now means to speak in probabilities that are isolated to the specific experiment itself. What do we think will be the result of this particular experiment right here, right now? No definitive knowledge is possible in this new version of scientific knowledge. To be clear, this is not the death of knowledge, but the death of a long-standing belief in what “reality” is like. Since Plato, reality is assumed to be stable, eternal, and transcendent of the here and now. What we experience is a mere shadow of what is real.

Inherent in Lyotard’s exposure of this aspect of the language game of science is a revaluation of Thomas Kuhn’s “normal science.” For Kuhn, normal science is not looking for breakthroughs. It is looking to confirm theories based on dominant paradigms. Normal science does not want to disrupt what we know so much as it wants to stablize what we think we already know. Much of physics and much of biology as research disciplines have gone to demonstrating that Einstein and Darwin, respectively, were right. These research projects, in other words, assume that reality is what Einstein and Darwin said it was. Research is designed to reinforce their view of reality, which makes science fundamentally conservative in its institutional approach to knowledge.

In the postmodern condition of science, however, reality isn’t what modernity thought it was. Normal science is no longer a conservative attempt to reinforce what we already think we know about reality. Postmodern normal science replaces a stable and demonstrable reality with an elusive reality that evades our grasp. In the case of quantum physics, reality is effected by and responds to our ability to pin it down. The attempt to measure something changes the thing you are measuring. Reality seems to be running away from us not because we have failed to discover the underlying stabilities, but because reality isn’t stable like we thought it was. To be sure, the former may be true — we may have not yet discovered the underlying stabilities. The important point here is that postmodern science is forced to question our modern Platonic biases about reality and truth. In doing so, previous assumptions about truth and reality need to be examined as the effect of language games. How and why did we assume that reality was stable and demonstrable? Heraclitus finally gets his revenge.

“Reality” is thus something very different in postmodern science, and this difference leaks into the general culture at large. If reality is no longer stable and knowable, it must be seen as open-ended. Once we see reality as open-ended, it’s a fairly short step to seeing it as open to our manipulation. For Lyotard, this can go in a couple of directions. If we have a desire to reimpose a closed system, this open-endedness will lead to increasingly excessive efforts to control reality — effectively to circumscribe all the possible behaviors so as to control them. This is the problem he sees in Habermas’ early use of consensus (Diskurs). It is an attempt to reimpose a metanarrative of emancipation by reducing the incommensurability of language games to a common yardstick — the normative rules of perfect agreement. The incommensurability is what Lyotard thought should be respected and embraced, not elided. How would that elision take place? Either through terror — the more or less violent exclusion of those who don’t play the dominant game — or through seduction — the unequal distribution of benefits to those who join in. Will you choose poverty or stock options? The choice is yours.

In a more positive direction, however, Lyotard wants us to embrace the possibilities that occur within this open-endedness. And here we arrive at openness and receptivity as fundamental dispositions that would keep the postmodern condition from falling into nihilism. We find in the last sentence what Lyotard has been driving at all along — a new way to think about the possibility of justice once metanarratives are obsolete and un-credible: “This sketches the outline of a politics that would respect both the desire for justice and the desire for the unknown” (67). The quest for knowledge within postmodern science has moved a way from deliberately seeking certainties (as in Kuhn’s normal science) to seeking “paralogy” — experimental results that don’t prove anything definitive. Instead, they produce results that show us how much we don’t actually know. They produce unknowns rather than Platonic truth. Again, Heraclitus gets his revenge on Plato. In the production of unknowns, postmodern science necessarily forces a discussion of the legitimacy of this pursuit. This manifests itself as a discussion of its own rules of engagement and makes those rules subject to debate. Once reality is no longer assumed to be stable and repeatably provable, it becomes disingenuous to try to reimpose certainty and stability into the game. The desire for certainty, like the desire for metanarratives, is incredulous and obsolete.

Thus we have within postmodern science a model of discourse that seeks the unknowable and exposes its rules to continuous justification. For Lyotard, this can be a model of social interaction that breaks from Habermas’ nostalgia for modern consensus:

Consensus has become an outmoded and suspect value. But justice as a value is neither outmoded nor suspect. We must thus arrive at an idea and practice of justice that is not linked to that of consensus. (66)

His point here is that consensus actually makes the idea and practice of justice impossible. As I said above, those who fall “outside” of the system will be subject to terror — either actively or passive-aggressively. The alternative is to hold onto justice as a value while giving up any preconceived notion of what that will look like in any given situation. This is Lyotard’s answer to the nihilism of the postmodern condition.

Justice is, therefore, “an idea and practice.” It is not and cannot be a “theory” that imposes itself on any given situation from above or outside the game. This is to reassert a metanarrative, which is what Lyotard thinks Habermas is doing with his notion of consensus. (I’m not going to go into whether or not this is a fair reading.) Consensus arrives in any agonistic discourse as an external ideal — an ideal that Habermas thinks is actually internal to language games as an inherent “communicative ethics.” Whether external or internal really doesn’t matter to Lyotard; it’s a modernist desire for systematic harmony and unity that will yield a conservative approach to sociopolitical interactions. To unlink justice from consensus is not to give up on either of them. It is to unlink justice from an over-arching theory of what it is that could then be imposed (by what authority and on what basis?) before the language games even begin (whatever we might be able to identify as a beginning).

The postmodern challenge (that was always embedded in modernism) is to take seriously “an idea and practice of justice” that precedes any legitimating and pre-defining metanarrative that would limit what could be considered “just” in any given conflict. This would require a radical openness to understanding and engaging any relevant situation requiring us to marshal justice as an idea and a practice. Instead of looking for a predetermined outcome — we will all perfectly agree eventually — we must undertake a “quest for paralogy” (66) as the quest to deliberately create the unknown and undecidable — to see knowledge as the attempt to solicit probabilities rather than repeatable proofs that reinforce what we think we already know. This would be to embrace incommensurability as the possibility of justice. This possibility exists as long as we make a commitment to justice as a moral disposition rather than a form of modern knowledge.

At this point, we need other sources to help imagine what the possibilities are. Lyotard — at least in The Postmodern Condition — is only scouting the frontiers of what a just society can be once our incredulity toward metanarratives takes relentless hold on our ability to legitimize any form of sociopolitical organization. Taking justice as idea and practice seriously requires us to think of ourselves in different terms — which are only hinted at in The Postmodern Condition. We are, as he says near the beginning, “nodes” in a network of interlocking language games. The self conceived in this way is not an atomized unit but is spread across and mixed into these networks. If atomization does occur, it is only as an effect, which is at the heart of his use of the term “terrorism.”

The challenge Lyotard raises is how to see ourselves in this postmodern condition as still having a desire for justice and still having the practical means of enacting it even if we don’t have prior justifications for what justice is. In other words, to be just toward each other does not mean to have a prior knowledge of what justice is. This requires us to seek a practical notion of a self that can see itself having agency in these networks even if our egos cannot be conceived as the stable center of any given nexus. In such a practical consideration of the self, we’ll need recourse to the notion of a soul as a capacity to control our responses. This soul would need to be fundamentally relational and not atomized. It would need both a powerful capacity for effort and action while also remaining radically open to how those actions reverberate through networks of language games.

To be sure, this ability to enact a value without being able to offer a definitive definition of what it is beforehand happens all the time. Most of us live by values that we can’t define. Nearly all of us can claim to have deep and long lasting friendships. But ask anyone to define what a friend is, and you’ll get wildly different answers even among mutual friends. It is not necessary to have a definition of friendship before one engages with the value. Same with love, compassion, sympathy, forgiveness and gratitude. We engage these values all the time without having clear definitions of them. This does not mean that we should build an ethics on these values as eternally “human.” This would be to play a tricky metanarrative game of good and evil (to mix Lyotard with Nietzsche). One could easily say that hate, anger, and revenge are human values too. Which ones should we choose to be the true representatives of humanity?

Such a definition is a fool’s errand, and unnecessary. If we take the “idea and practice of justice” seriously, we’ll need to lean on these practical aspects of how we enact our values. This enactment involves dispositions rather than dogmatic definitions. It involves orientations rather than systems of belief. It requires us to turn our attention to people who can serve as examples for this kind of practice — people who have thought about incommensurability as the possibility of justice in practical terms.

To close this meditation, and to perhaps transition to another line of thinking, this radical openness of the soul is, I believe, a very helpful way of thinking about the kind of self that Lyotard finds in our postmodern condition. It is similar to the way Simone Weil envisioned “the love of neighbor” as an “implicit love of God” and the equivalent of justice. When she asks, “What is your malheur?” she models what Lyotard advocates in respecting incommensurability. (Maybe it is more proper to say that Lyotard is modeling her.) One must meet the other’s answer to this question by “emptying your soul” so that you can fully receive the answer and be changed by it. This is “love in the void” as she called it. It is the faith that we can hold these values (love and justice) as dispositions and orientations to situations that are fundamentally unknowable — even if we don’t have the definitions of love and justice ahead of time. In fact, it is crucial that we don’t have those definitions, as they cut off our ability to truly attend to the answer.

Thus, to ask the question, “What is your malheur?” and to greet it with a non-egoistic self-emptying is paralogy in action. It is the attempt to solicit the unknown into view so that it can be experienced and discussed — but discussed on its own terms without a prior imposition of categories or rules of consensus. Language games as games of power and resistance — “agonistics” — must become part of how we listen and interact in these situations if we are avoid the modernist tendency to see malheur as a nostalgia for a lost unity.