The Return of Fate

Our attempts to build a world we control has led to much that is out of our control

Summary: This essay explores how fate—the domain of what eludes direct control—returns under conditions where we have expanded our capacity to steer the world. It argues that our computational mastery creates unintended consequences that feel like fate turned inside out, and that moral life today requires navigating these emergent conditions.

The aftermath of the Marshall fire in Superior and Louisville, Colorado, 2021

Historical Emergence of Computational Mastery

In my Substack essay series on our Enlightenment legacies, I’ve argued that we’ve made computational power into the motor of history.

We can understand the Enlightenment as a chapter in humanity’s confrontation with fate—the things that lay beyond our control, such as disease, famine, wars, scarcity. In the eighteenth century, we stared into their opacity, turned them into issues to be studied and, to the degree possible, made them tractable to computation as a means to either eradicate them or mitigate their worst effects.

As this history has continued, our computational power has greatly expanded: we are steering things we didn’t used to steer as the philosopher and historian of science Michel Serres once claimed.

These issues are are further explored in The World as Computation, where computation becomes the environment in which fate is reconfigured.

Unintended Consequences as the Return of Fate

As we have gained greater mastery over fate, it has led to a strange return of things out of our control—climate change, pollution, destabilized democracies, viruses that globalize in weeks, whole towns and suburbs wiped from the landscape by fires.

It feels like fate is turning inside out.

But these new forces are the unintended consequences of our own making, and they pose an unprecedented moral question also voiced by Serres: how can we master our mastery of nature?

Stoic Fortuna as Fate

Writing as a mentor to Lucilius in the first century CE, Seneca lays out the classic Stoic understanding of fate, humans, and the gods. His vision is that all the events of the world are in the control of the gods, and the human good is to accept fate with a calm tolerance:

You admit that the good man must of necessity be supremely respectful toward the gods. For that reason he will calmly tolerate anything that happens to him, for he knows that it has happened through the divine law by which all events are regulated. If that is the case, then in his eyes honorable conduct will be the sole good; for that includes obedience to the gods, neither raging against the shocks of fortune nor complaining of one’s own lot but accepting one’s fate with patience and acting as commanded.1

This morality is born of a world where most everything is beyond human control—fires, floods, earthquakes, wars, enslavement at the hands of victors, chronic pain, disease and all the other risks of living that come along with being human.

Elsewhere Seneca will make clear that gods is just another word for natural causes. In either case, Seneca is reminding Lucilius that most everything is beyond our control, and we might as well accept that our power is limited.

Gods, natural causes, divine law, fortune are all words that place a strict limit on what humanity can hope for and what we are responsible for.

In the ongoing struggle between man and nature, nature has all the power and all the control. The only thing that Seneca believed we could be responsible for, as he continually makes clear in his Letters, is our honorable conduct—the acceptance of the inevitability of what happens, and that one should never get too upset about it.

See my short reflections on how ill-equipped our traditional moralities are for where we are now: ‘Purpose in Motion’.

Modern Control Sequences

In many ways our world resembles Seneca’s. Fate seems to have returned in the form of nuclear weapons, climate catastrophes, global pandemics, wildfires wiping out entire towns, software making decisions at computational speeds well beyond human perception.

But the control sequence is different. For Seneca, the world exists with its own natural causes that are impervious to human activity—all we can do is respond virtuously. Control beyond self-control is not in the offing. At best, one can cope with the ups and downs of fortuna.

We live a different control sequence today. If we face out-of-control circumstances, these are often the byproduct of our attempts to control fate.

December 30, 2021

The 2021 Marshall Fire in Colorado does not fit Seneca’s worldview. The control sequence is different. Suburban neighborhoods in Louisville and Superior, like most of our built environments since the Enlightenment, were designed for stable and predictable lives. On December 30, 2021, the cities faced very high winds on a bone-dry day with temperatures in the mid-50s. Sparks from an underground coal seam and a nearby property became flames. Residents had only minutes to flee as more than a thousand homes were reduced to ash in a few hours.

Where does one draw the line between natural and artificial causes? The engineering meant to facilitate stable and predictable lives fueled the fire’s speed.

Even if we stare inside the flames, we find an indecipherable mixture of nature and technology.

. . . when human-made materials like these burn, the chemicals released are different from what is emitted when just vegetation burns. The smoke and ash can blow under doors and around windows in nearby homes, bringing in chemicals that stick to walls and other indoor surfaces and continue off-gassing for weeks to months, particularly in warmer temperatures.2

From the abnormal December weather to the speed, spread, and composition of the flames, we are the authors of this fate—a fate that lingers on walls and off-gasses for years after the flames are extinguished.

We’ve formatted the world, unintentionally of course, for this to happen. Our attempts to control fate yield moments when we lack control.

We can pretend that we don’t control these things and adopt a Stoic’s attitude of virtuous acceptance. But that is to ignore the moral question of our time out of joint: how do we master our mastery of fate?

Imaginary Gods and Literal Agency

When Seneca writes to Lucilius, ‘You admit that the good man must of necessity be supremely respectful toward the gods’, his use of gods can be understood as figurative language for natural causes. Elsewhere, we find Seneca more perspicuous on this point. In ‘On Earthquakes’ he writes: ‘. . . neither the sky nor the earth is shaken by the anger of divinities: these things have their own causes.’3

To think of the gods as divinities with human emotions and intentions is a sign of one’s ignorance: ‘When we are ignorant of the truth, everything is more terrifying, especially when rarity increases the fear.’4 Seneca typically uses godspositively, but only as a figurative way to describe more literal natural causes.

We have inherited this figurative view of gods in a long history that stretches from Epicurus, Lucretius, the Stoics, and others. Our self-described secular age sees all gods as imaginary. Any expressed belief in God is treated as a delusion, the result of irrational ignorance.

The problem for our current era is this: we are ignoring the literal creation of new gods. Because our secular age lacks the theological sophistication of the Middle Ages, we are missing this crucial development, which risks creating an actual, literal class of humans that may look more like Homeric gods than we should want:

The gods have spun for all unlucky mortals

a life of grief, while nothing troubles them. (Iliad, 24.525-26, Wilson trans.)

Literal Gods

Let’s bring this back down to earth.

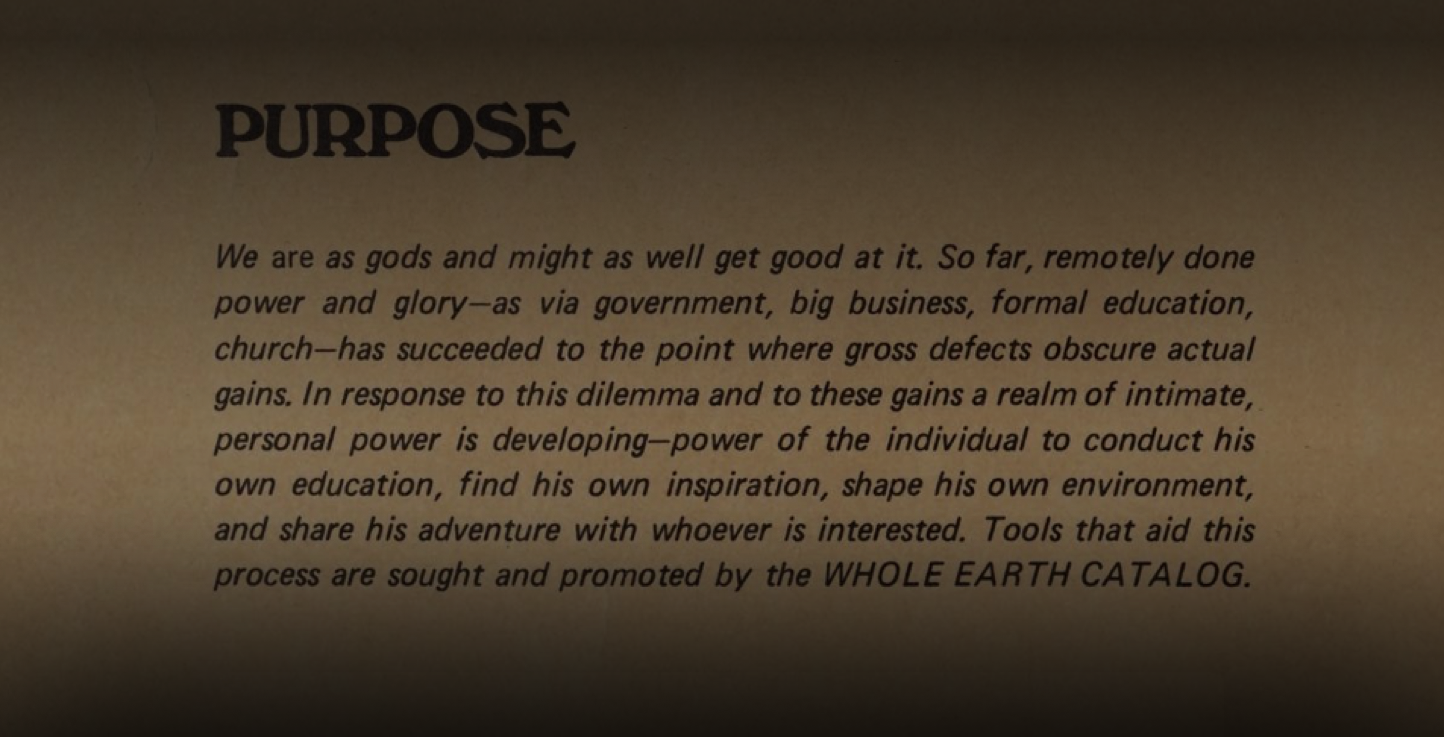

When in 1968 Stewart Brand launched The Whole Earth Catalog, he captured its purpose statement in its first sentence:

We are as gods and might as well get good at it.5

Is this a figurative invocation of gods? Yes. Is this a literal invocation of gods? Also, yes. This single sentence concentrates the transition to a new era that is easily missed in our secular age.

The transition might actually come down to a single word—as versus like.

If Brand would have written ‘We are like gods’, the figurative would have been left in tact. But I wish to see deliberate intent in his use of as. In English, as has many grammatical operations: comparative (‘as tall as’), synchronizing actions (‘he was dancing as it was raining’), and prepositional (‘as teacher, she guided us through the math lesson’). None of these meanings are figurative or metaphorical. As makes a literal connection among the parts in the sentence.

In Brand’s phrase, as can be replaced with ‘functioning in the capacity of’ (‘as the teacher’), and we could easily translate the sentence inelegantly as ‘We are functioning in the capacity of gods and might as well get good at it.’

The actual phrasing turns Seneca’s world inside out while leaving it relevant and recognizable today. It feels to me like the older worldview is being pulled through a keyhole, and in the process a new worldview emerges that has the power to deify some individuals as actual, literal, living gods.

This returns us to questions explored in Life at the Speed of Computation and Fate, Computation and the End of Christian Time about how tempo, history, and ethical life are shaped by calculative infrastructures.

Theodicy and New Responsibilities

In an era where we are deifying literal gods, it seems prudent to rejuvenate some theological concepts that have been shunted to the sidelines in our atheistic Modernity. Theodicy is one such term.

Theodicy is the attempt to justify how a loving God created a world that allows evil and suffering to exist. Flipped on its head, it is a way for humanity to put God on trial—if you love us and are all-powerful, why do we suffer?

In a worldview that imagines God and can only experience religion through irrational faith, theodicy remains an intellectual concept abstractly debated over by theologians. When gods are real, however, theodicy comes down to earth.

If we have the power to end hunger and mitigate disease, why don’t we?

When some living, breathing human beings are suddenly ‘as gods’, we are in the realm of the literal, and theodicybecomes questions that can be posed to those on whom this power has been conferred.

Again, how will we master our mastery of fate?

We are accustomed to calls for slowing down the pace of innovation. But is this an automatic good? It has been the bias of our moralities for centuries. What will be the new fate issued by slowing down? Will it will lead to scapegoats and accursed shares for those who are asked to wait while our institutions repair themselves—or we invent new ones—capable of envisioning progress once again?

Explore this cluster of essays:

Fate, Computation and the End of Christian Time – historical shifts in time and meaning

Life at the Speed of Computation — tempo and moral frameworks

Reading le Grand Récit — essays on the later works of Michel Serres

Footnotes

1 Seneca, Letters on Ethics, No. 76. translated by Margaret Graver and A.A. Long.

2 Colleen E. Reid, ‘3 years after the Marshall Fire: Wildfire smoke’s health risks can linger long-term in homes that escape burning’

3 Natural Questions, ‘On Earthquakes’ 3.1.

4 Ibid, 3.2

5 The full citation of the title page of the first edition, Fall 1968, reads: ‘We are as gods and might as well get good at it. So far, remotely done power and glory—as via government, big business, formal education, church—has succeeded to the point where gross defects obscure actual gains. In response to this dilemma and to these gains a realm of intimate, personal power is developing—power of the individual to conduct his own education, find his own inspiration, shape his own environment, and share his adventure with whoever is interested. Tools that aid this process are sought and promoted by the WHOLE EARTH CATALOG.’ This text can be found at the Whole Earth Archive.