Reading Zarathustra: The Three Metamorphoses

In my last commentary on Book I, I did not address the first of Zarathustra’s speeches — ‘Of the Three Metamorphoses’. If anyone has read, or heard of, any part of Zarathustra, it is often this speech. While taking the form of a parable, it is a remarkably clear statement of what Nietzsche thinks about moral transformation freed of the constraints of Cartesian rationality.

At the heart of this challenge is the oscillation between Yes-saying and N0-saying.

Metamorphoses

Zarathustra’s opening lines set out a composition of time that is neither pure becoming nor pure being. It is a composition of time as ‘metamorphoses’.

Three metamorphoses of the spirit I name for you: how the spirit becomes a camel, and the camel a lion, and finally the lion a child.

We will be tempted to read a progression in this single sentence, especially in the ending ‘finally the lion a child.’ Such a reading would give particular weight to the end point, which would mean treating the verb ‘becomes’ as purely transitional between states.

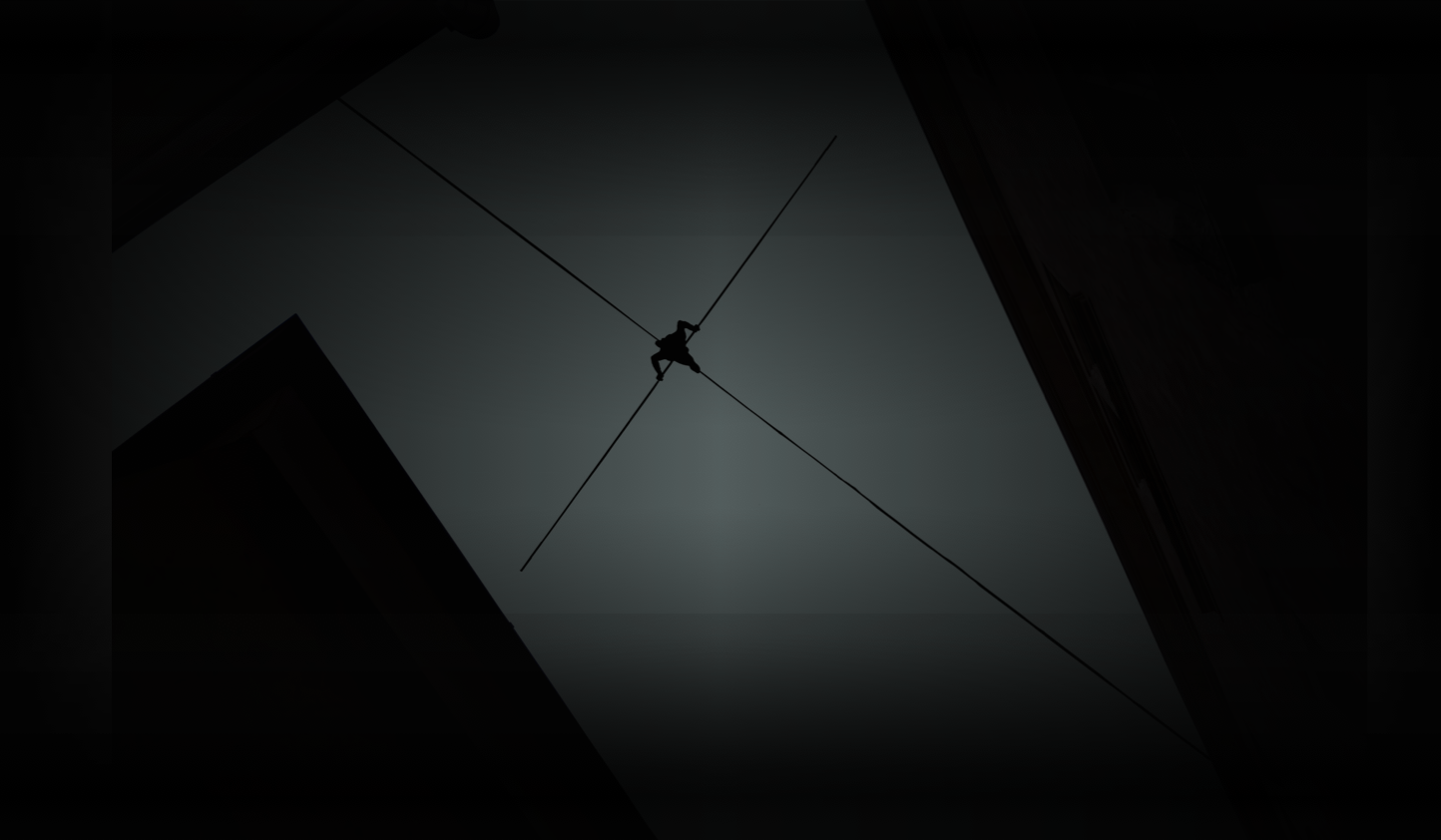

This linearity seems out of tune with the remainder of Zarathustra’s message. End states are an accute problem for Nietzsche’s Zarathustra. The tightrope walker, as we have dwelled upon many times in Time as Practice, embodies this capacity for our own entrapment in the in-between as its own end state. The tightrope walker is not without some aspect of the overman, but he gets stuck as an entertainer for the herd of Last Men: ‘You made your vocation out of danger, and there is nothing contemptible about that. Now you perish of your vocation, and for that I will bury you with my own hands’ (Prologue 6).

We have in this encounter with the tightrope walker Zarathustra’s first clear communication of the camel — the spirit that wishes to carry others’ burdens. Zarathustra will carry the dead body of the tightrope walker through the remainder of the Prologue. Only when he lays him in the hollow of the tree do we arrive at the possibility of Zarathustra’s own transition from the camel to the lion.

‘On the Three Metam0rphoses’ is, therefore, about metamorphoses, not states of being. The speech is not entitled ‘On the Three States of the Soul’, which would have been easy. Zarathustra’s message, even at this early stage of the book, is not easy. It is not a spiritual progression from state to state.

Becoming is not subservient to Being. Nor is Becoming just another form of Being, as it was for the tightrope walker. Zarathustra is up to something far more radical with respect to metamorphoses.

‘Metamorphoses’ could be about about relative stabilities of the soul, or it could be about capacities of the soul. Emphatically, metamorphoses cannot be about end states, nor should we see it as states of a purely linear evolution. If the finality of the child is an end state, it is finality only insofar as the soul of the child has not hardened into the camel nor gotten stuck in the in-between of the powerful N0-saying of the lion. At the same time, we need not see the states of the soul as mutually exclusive. This would tempt us to build in renunciation as the mechanism of transition, which runs counter to Nietzsche’s view of subjectivity.

The lion has no need to renounce the camel; nor is the child the renunciation of the lion.

If renunciation does not drive metamorphoses, then the sacred No-saying of the lion emerges within the burden carrying power of the camel. More than this, it augments the power of the camel. Likewise with the the sacred-Yes saying of the child: it has to retain the strengths of both the camel and the lion within the childlike disposition to the world. If we attend to the sequence, the child comes at the end, which can be understood as recovery of an earlier state, but that recovery retains aspects of the former states. Metamorphoses would be neither linear transitions between these states nor a chaotic and frenetic movement that lives in a constant indeterminacy among them.

Impasse and Great Health

We must retain the notion of great health in our reading of Zarathustra, especially here in the parable of metamorphoses. Great health is the manifestation of the will to power that keeps us as a kind of helmsman navigating the unpredictable fluctuations of the sea.

The camel need not seek the lion as its meaning; nor does the lion seek the child as its meaning. Rather, these are conditions of the soul that are necessary for the navigation of life.

These relative stabilities of the soul must be embraced authentically if one is to effectively transition and not get stuck like the tightrope walker. For the camel to become a lion and for the lion to become a child, one needs to take seriously each of these metamorphoses of the spirit. One has to be the camel because one is playing out a key feature of the spirit: it rejoices in its strength.

This metamorphosis must happen, otherwise the camel ends up overweighted with the burdens heaped upon it. Without the transition, the spirit of the camel becomes ossified into an identity entrapped within the moral experience of ‘Thou shalt’.

What Nietzsche describes throughout this section can be understood as impasses. The strength of the camel is embraced as strength, and the N0-saying of the lion emerges from the impasse of the camel being a camel. This is different than an impasse that arises through the conscious pursuit of deconstruction. We see the latter in Nāgārjuna’s MMK: ‘The intention of Nāgārjuna is to bring us to an impasse so that we see for ourselves that the intellect is not ultimately capable of taking us anywhere’ (Thich Nhat Hanh, Cracking the Walnut: Understanding the Dialectics of Nāgārjuna, 18). This impasse is forced by pursuing the logical impossibilities of Nāgārjuna’s imagined opponents. The repetition of impasses in the structure of Nāgārjuna’s verses is an intentional strategy that should, when one authentically grapples with pratityasamutpada (conditioned origination), yield a mode of experience that has no need for essences (sunyata).

The impasses that Nietzsche’s Zarathustra captures in this parable come from exhausting the possibilities of a commitment to one of the states of the soul. The camel becomes too loaded down, and the No-saying of the lion emerges from the exhausted strength. The No-saying of the lion gets trapped in its own impasse where No-saying is in danger of becoming ressentiment. The child emerges from this impasse of the lion.

We shall return to the metamorphosis from lion to child, but for the moment I want to look at another place where Nietzsche captures this kind of impasse that is not renunciation.

Brief Habits

Nietzsche has a beautiful aphorism on the authenticity of relative stability in GS 295, ‘brief habits’.

Brief habits. — I love brief habits and consider them as invaluable means of getting to know many things and states, and right down to the bottom of their sweetness and their bitterness;

Pausing here for a moment, we should recognized that Being/Becoming is a poor way of understanding the composition of time Nietzsche has articulated in this single sentence. If we treat this as the temporality of metamorphoses, we see a blending of intensity and transition where an identity emerges that is tied to the habit. But we shouldn’t get stuck like the tightrope walker, which would mean that our brief habits have become enduring habits:

I hate enduring habits and feel that a tyrant has invaded my space and that my life’s air thickens…

Here again we have a clear statement from Nietzsche about the fixity of Being in an ossified state. The brief habit becomes an enduring habit when it exercises a tyranny over the soul — it has become an obligation: ‘for example through an official duty, through constant intimacy with the same people, through a permanent residence, through a consistent state of health.’

Brief habits are not, however, undertaken superficially or cynically. Brief habits are about ‘getting to know many things and states’ in their deepest senses — ‘their sweetness and their bitterness’. Therefore, the brief habit must appear to be real and eternal when it is undertaken:

I always believe this will satisfy me all the time now — even a brief habit has this passionate faith, this faith in eternity — and I am to be envied for having found and recognized it.

A brief habit is the positive experience of eternity in its salvational power. Yet it remains temporary but not with an imposed time limit. There is no set timer or a stamped expiration date. The expiration may or may not happen, but if it does, it is a peaceful one:

And then one day its time is up: this good thing takes its leave of me, not as something that now makes me nauseous — but peacefully and stated by me, as I am by it, and as if we should be grateful to one another and so shake hands in parting.

Nietzsche ends this aphorism by emphasizing that this mode of experience is not fickle. About this, he is very clear:

However, the most unbearable, the genuinely terrifying thing to me would be a life lived without habits, a life that constantly demanded improvisation: — this would be my exile and my Siberia.

We have in this aphorism a temporality of experience that is neither Being nor Becoming. These are not Nietzsche’s terms. They do not allow for the beautiful articulation of experience that is contained in GS 295, which I believe is the same temporality of experience articulated in ‘On the Three Metamorphoses’. We live with an intensity that experiences eternity without trying to grasp and hold that eternity such that it becomes a tyranny.

From a Mahayana Buddhist perspective, the brief habit may have moments of grasping that lead to dukkha, but when the grasping becomes a desire for permanence, a brief habit becomes the tyranny and thickness of an enduring habit. But a life lived without habits — ‘a life that constantly demanded improvisation’ — is equally tyrannical. It is the life of the tightrope walker who is so fragile that ‘a jester can spell its doom’ (Prologue 7).

This experience of brief habits enjoys intense states of being, and treats them as eternal and as end points, but the soul remains open to further metamorphoses because we accept that at some point ‘one day its time is up’.

This is the definition of great health: we are all-in on what we are doing, and we may deeply believe that we have found the permanence of the thing itself. But when that permanence reveals itself to be impermanent, we need not become anxious or distraught or indifferent. Rather, we are the helmsmen guiding the ship. At times the sea is rough, at times smooth. Our attention, however, is stretched between the eternity of the deadly storm we need to manage right now and the destination to which we are navigating. Attention goes where it needs to go as we navigate. And if, like Pliny the Elder making his way across the bay from Misenum to Pompeii, a change of destination is required of us, then we make it so. ‘He paused for a moment wondering whether to turn back as the helmsman urged him. "Fortune helps the brave," he said, "Head for Pomponianus”’ (from Pliny the Younger’s Letter 1 on Pompeii to Tacitus).

Time Trialing

A personal example: I used to be a pretty good time trialist in the sport of cycling. I was an amateur, but I did manage to win a state championship for my age group in 2009. At the time, I deeply believed that I would always be a time trialist. I couldn’t have been successful if I hadn’t believed that my commitment was forever. Today, I no longer time trial, and I have long since sold my TT bike. Time trialing ended up being a ‘brief habit’.

Was I delusional? No. Brief habits do not contain within them the ‘as if’ falsity of fake beliefs. I believed I would do this forever, and this belief was essential to being good at this sport. It became an identity. But around 2011 we both shook hands in parting. I am not remorseful or glum about the separation. I don’t look back and think that I was deluded because from my current vantage point I was clearly wrong about ‘forever’.

These are the best of experiences — we’re committed even though we realize that the commitment might wander off some day.

This temporality of brief habits is what I believe Nietzsche’s Zarathustra has in mind when he speaks of metamorphoses. In order for the camel to become the lion, there must be an intensity to the camel that drives its own metamorphoses.

Let’s not call this intensity identity, though it can be experienced as such. Nor is it the identity of a permanent state of becoming like the tightrope walker.

The camel, however, can’t just become the child. This would be to skip an important step. A child that lacks the ‘sacred No-saying’ of the lion is a purely passive sponge soaking up whatever the culture gives her. The lion’s sacred No-saying must emerge from the spiritual exhaustion of the camel — i.e., its impasse. Just so, the impasse of only No-saying by the lion must exhaust itself so as to become the metamorphoses of the child.

To create new values — not even the Lion is capable of that: but to create freedom for itself for new creation — that is within the power of the lion.

To create freedom for oneself and also a sacred No to duty: for that, my brothers, the lion is required.

This is crucial to understand for those interested in the ‘psychological problem’ of Zarathustra that Nietzsche describes in Ecce Homo. The passage is worth quoting at length:

The psychological problem with the Zarathustra-type is how someone who says No to everything to an inordinate degree, does No to everything to which hitherto everyone said Yes, can nevertheless be the opposite of a No-saying spirit; how this spirit bearing the weightiest of destinies, a fatality of a task, can nevertheless be the lightest and most unworldly — Zarathustra is a dancer — ; how one who has thought the ‘most abysmal thought’ nevertheless finds in it no objection to existence, not even to its eternal recurrence — but rather, yet another reason to himself be the eternal Yes to all things, ‘the immense unlimited yes- and amen-saying’ . . . ‘I still carry my yes-saying blessings into all abysses’ . . . But that is the concept of Dionysus yet again.

To move from the camel to the child, one must cultivate the sacred No-saying of the lion. The use of ‘sacred’ is important. It is Nietzsche’s attempt to differentiate the necessity of the lion’s No-saying from the kind of No-saying that activates ressentiment, which will become the central theme of the Genealogy only a short time after the publication of Zarathustra.

For No-saying to be sacred, it must keep close company with Yes-saying: ‘yet another reason to himself be the eternal Yes to all things’. We must read ‘the eternal Yes’ as the same ‘eternal’ we find in ‘brief habits’ — an intense experience of eternity that may itself be temporary and transitional.

To understand this mixed up temporality where the experience of the eternal drives metamorphoses, we must descend into the transitions that Zarathustra describes in ‘On the Three Metamorphoses’.

‘Thou Shalt’ and ‘I Will’

Let us now return to the problem of impasse and its power of metamorphoses. The first thing that we should note is that lifting the weight of culture can only be done by strong souls that have been willing to bear the weight in the first place.

They bear it because, at least initially, they want to bear it. It is their nature:

Its strength demands what is heavy and heaviest.

What is heavy? thus asks the carrying spirit. It kneels down like a camel and wants to be well loaded.

What is heaviest, you heroes? thus asks the carrying sprit, so that I might take it upon myself and rejoice in my strength. (16)

The camel is not conscripted into service by its masters, although it is a beast of burden. It willingly enters into this burden because that is the nature of its ‘carrying spirit’.

Strength is key here, and not everyone can be a camel. The herd of Last Men have no capacity to be camels because their spirits are not strong. They don’t wish anything to be a burden to them. ‘One no longer becomes poor or rich: both are too burdensome’ (Prologue 5). They seek a mediocre middle.

We must also attend to the use of heroes in this passage. The camel wants to be the bearer the heroes’ burden. He will make himself their beast of burden — the servant, the victim — that makes the heroes able to be heroes. In doing so, the camel takes on a role somewhere between hero and victim.

It is not a single burden that the camel chooses to bear. The repetition of the ‘Or is it’ questions sets the pattern of always accepting more and more of the burden even as the terms of the burden change. The camel becomes the pure carrying power of any cultural burden the would-be heroes devise. In each acceptance, the camel gives something up: ‘Or is it this: loving those who despise us, and extending a hand to the ghost when it wants to frighten us?’

The result is that the camel’s carrying spirit ‘hurries into its desert’. It is a desert of its own making:

All of these heaviest things the carrying spirit takes upon itself, like a loaded camel that hurries into the desert, thus it hurries into its own desert’ (my emphasis).

This last point is crucial. The camel’s self-imposed desert is squeezed out of the repetition of its willingness to pile on the burdens. The desert is produced by the great weight of culture piling up on the back of the camel.

The desert can be seen as a deliberate choice. The first monks of the fourth century, following Anthony’s rigorous example, adopted the cultural practice of anachoresis and left behind the often violent burdens of life as a village farmer. Anachoresis — withdrawal — thus became a spiritual practice adapted from the cultural practice of simply moving one’s farm away from the village. From Anthony’s example, an entire lineage of Egyptian monks emerged who perfected the spiritual practices of anachoresis in the desert. [1]

This desert is neither being nor becoming. We cannot find the hard separation. It is the tightrope strung between the tower of carrying burdens and some other tower that is not yet understood by the carrying spirits. It just knows that the weight has become so great, that the burden now appears as a dragon.

But in the loneliest desert the second metamorphoses occurs. Here the spirit becomes lion, it wants to hunt down its freedom and be master in its own desert.

Here it seeks its master, and wants to fight him and its last god. For victory it wants to battle the great dragon.

Who is the great dragon whom the spirit no longer wants to call master and god? ‘Thou shalt’ is the name of the great dragon. But the spirit of the lion says ‘I will’.

The sequence from ‘Thou shalt’ to ‘I will’ is important because it is not only linear. The ‘I will’ does not come after the ‘Thou shalt’ as its creation. This would lock the will inside of ressentiment. If it were purely the creation of ‘Thou shalt’, the will would only be able to express itself as a new ‘Thou shalt’ that would ossify into a new dragon.

The ‘I will’ is present in the camel, but it appears only as the expression of its strength. The camel experiences his will as a duty to his strength and to the heroes that he wishes to support. The camel thus traps himself in his own desert. It is only in the transition between camel and lion that ‘I will’ can be experienced as a will to freedom.

In fact, we can read the ‘I will’ as the metamorphoses itself. It is nothing other than the activation and realization of its existence that does not need to be burdened as only ‘Thou shalt’.

The freedom is, therefore, not pure freedom of the will, but it is a will that ‘wants to hunt down its freedom and be master in its own desert.’ This is simultaneously realization — i.e., the camel has always had a will — and transformation — i.e., the camel is becoming the lion that is capable of No saying to the incessant piling on of the burden.

We need not see punctuated points in a linear progression. This is not Zeno’s arrow that gets stuck in the impossibility of motion because time is broken up into punctuated instances of space. Again, this is not the tightrope walker who can’t move forward or backward on the line of the tightrope.

The Great Dragon

What is the great dragon? It is the pure ossification of experience into the performance of duty without any ability to recall or experience the acceptance of the duty as requiring the ‘I will’:

‘All value has already been created, and the value of all created things — that am I. Indeed, there shall be no more “I will!”’ Thus speaks the dragon.

In short, the great dragon is the figure for the ‘I will’ that can no longer see itself as anything other than ‘the strong carrying spirit imbued with reverence’. This ‘I will’ is subsumed into the ‘Thou shalt’ such that it loses the capacity to experience itself as the human capacity that created the dragon in the first place.

Zarathustra seeks to undo this ossification of values. Any hardening of values into a great dragon reduces the ‘I will’ to the duty to carry a burden. The ‘Thou shalt’ stands in the way of the power of the ‘I will’ to create new values because it channels the ‘I will’ into the acceptance of another’s values.

We need not understand the ‘Thou shalt’ of the great dragon as repressing the ‘I will’. This way of reading Nietzsche would treat the ‘I will’ as a power that has an essence that could be repressed. Something far more complex than the return of the repressed is called for. This will become more clear as Zarathustra articulates later the doctrine of Eternal Recurrence, but we are not there yet.

For the moment, we should understand the relationship between the ‘Thou shalt’ and ‘I will’ not as simple repression but as redirecting the ‘I will’ into the burden-carrying strength of the camel that the dragon turns to its own ends. In the Genealogy, the dragon will become the ascetic priest, and in the remaining speeches of Zarathustra, we will see different variations of this priest/dragon: ‘The Hinterworldly’, ‘The Despisers of the Body’, ‘The Teachers of Virtue’, and red judges among others. All of them believe that they have discovered the eternal virtues and thus require all acts of ‘I will’ to become the carrying of the burden of ‘Thou shalt’ as they have discovered it.

They shut down the need to create new values and thus shut down the need for any metamorphoses other than the becoming of camels. But in the act of creating camels, they must call forth and channel the power of the ‘I will’.

No-saying and Freedom

We must not lose sight of the danger of tightrope walking as we understand metamorphoses.

The camel steps onto the tightrope when it finds the lion of its ‘I will’. The lion is a N0-saying power that activates the ‘I will’ in opposition to the burden of the camel. It is important that the figure of the tightrope walker preceded this speech. If the lifting of the weight of culture requires the N0-saying of the lion, then the danger in the transition from camel to lion is that we embrace N0-saying as the only power of the ‘I will’.

This is the road to ressentiment.

The lion must be transitional to the child, and it can be so only by being a Yes-saying power and No-saying at the same time. Like brief habits, there has to be the intensity of experience that blends, imperceptibly, the eternal and the temporary.

There is difficulty in the transition. How would the lion know that its No-saying must be Yes-saying?

How do we recognize when ressentiment is conditioning our No-saying because so often it feels like Yes-saying? Ressentiment, as imagined or weakened vengeance, often feels like justice and rightness, therefore it feels like Yes-saying.

How do we get from the lion to the child? Why is the creative power that of the child?

These aren’t linear questions They seem to flood in together, and taken simply as questions they need not be answered in order to bring about metamorphoses. Yet we must seek answers if we do not wish to become tightrope walkers. Zarathustra’s only provocation at this point is to present us with a parable that prompts these kinds of questions. ‘Pay attention, my brothers, to every hour where your spirit wants to speak in parables: there is the origin of your virtue’ (57).

Innocence and Forgetting. Denigration and Ressentiment

The child receives the shortest treatment in this parable. Yet it is the most challenging to understand.

But tell me, my brothers, of what is the child capable that even the lion is not? Why must the preying lion still become a child?

The child is innocence and forgetting, a new beginning, a game, a wheel rolling out of itself, a first movement, and sacred yes-saying.

In the Genealogy, Nietzsche will dwell on forgetting as the power not to be permanently overtaken by ressentiment. It is a strong power and evidence of great health in a person. It is not forgetfulness as we would typically understand it. It is the power not to hold onto what may appear to be slights and insults. It shrugs them off and moves on.

Here in the figure of the child, forgetting is a power that always allows for new beginnings. This is the opposite of ressentiment, which accumulates the past into the present in such a way that the self becomes the center of everything. Ressentiment, when embraced as a permanent reaction, treats Eternal Recurrence as the accumulation of weight. It arises from not just no-saying, but from hatred and denigration.

‘A wheel rolling out of itself’

I started this post by arguing that Zarathustra is not laying out a progression from camel to lion to child. When thinking about metamorphoses as a composition of time, this progressive linearity is not part of Nietzsche’s worldview.

This does not mean the time of Eternal Recurrence is a wheel. This would be easy if this is what he meant. In fact, in describing the child, he calls this metamorphosis ‘a wheel rolling out of itself’. We must be careful, therefore, in defining Eternal Recurrence as the permanent rotation of a wheel around a single axis. As the wheel of Eternal Recurrence rolls, it rolls out of itself as it moves forward.

Zarathustra is building a bridge. We should not see the three metamorphoses as a wheel cycling among three stops. This would mean smuggling in a wheel of permanence that would short circuit any real commitment to impermanence.

Later, in ‘On the Vision and the Riddle’, Zarathustra will complicate the relationship between the circular motion of a wheel and the experience of time as Eternal Recurrence. He will emphatically disavow experiencing time as circular motion, which would simply mean seeing time as already determined and everything is merely passively parading through the gateway of Augenblick.

To see time as the motion of a wheel that rotates from arising to arisen to disappearance is to treat philosophy as Boethius did —as consolation. For Nietzsche, consolation is aligned with self-pity and renunciation. It therefore cannot in any way drive metamorphoses. Philosophy becomes the passive contemplation of time passing as a wheel of impermanence. We treat the coming and going of the points on the wheel as modes of experience that release us from Yes-saying and N0-saying.

This is not the intent of Eternal Recurrence. As we’ll see, and as Heidegger made clear in his lectures on Eternal Recurrence, the point is not to sit on the sidelines passively watching the wheel go ‘round and ‘round.

‘All that is straight lies,’ murmured the dwarf contemptuously. ‘All truth is crooked, time itself is a circle.’

‘You spirit of gravity!’ I said, angrily. ‘Do not make it too easy on yourself! Or I shall leave you crouching here where you crouch, lame foot — and I bore you this high!’ (126)

Taken as a mode of experience, Eternal Recurrence places our experience at the moment of Augenblick — where the line of the past and the line of the future meet. What we chose to do at any moment becomes part of our past that structures our future. If we see time as a wheel of fortune or impermanence, then we easily abdicate any agency through N0-saying or Yes-saying. We assume that time is out of our control and that the wheel will continue to spin with or without us.

This would require making ourselves into the dwarf where time cannot move forward, but it is stuck in a permanent rotation where impermanence is simply the endless repetition of the same cycle through states of arising, being, and dissolution. ‘All truth is crooked, time itself is a circle.’ The danger is that the wheel flattens all experience into this endless repetition. Nothing matters because it is impermanent.

Is this the same dwarf who, by leaping over the tightrope walker, caused him to fall to his death? Is the tightrope walker’s being stuck between towers equally at issue in ‘On the Vision and the Riddle’?

As should be clear from our reading of Nietzsche’s brief habits, impermanence experienced this way is inherently cynical and passively nihilistic. Renunciation, and pity are the moral consequences of experiencing time this way.

But, as we saw with the Great Dragon, the circle easily become the demand for an end of history — an enduring habit or an end to all ‘I will’ because the final ‘Thou shalt’ has arrived.

Nietzsche’s ‘wheel that rolls out of itself’ is the image of Eternal Recurrence that we must attend to in our reading of Zarathustra. The Books and Chapters themselves will enact this structure as the repetition through the experience of Zarathustra becomes metamorphosis playing out in the narrative.

Footnotes

[1] See Peter Brown, The Making of Late Antinquity, especially his third lecture, for a discussion of this adaptation of anachoresis by the monks around Alexandria in the fourth century CE.