Bataille, Religion, Experience

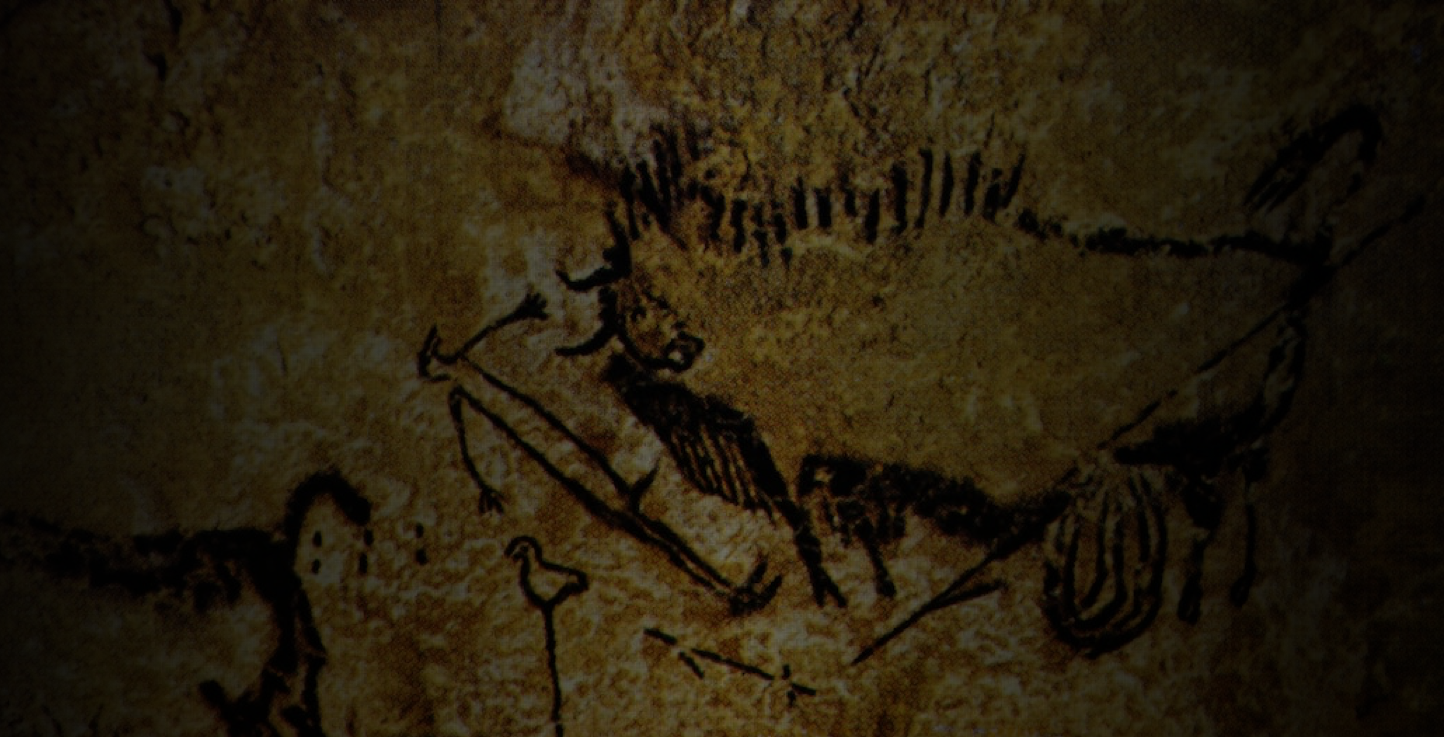

The bird man of Lascaux

This essay begins an engagement with Georges Bataille on the question of experience and religion that is beginning to feel crucial to me in our current incandescent moment. This moment is feeling like something equivalent to other moments in human history when the trajectory of time was undergoing complete redirection. Such times are turbulent because the branches and bifurcations are multi-directional, disorienting, and unstable.

Outcomes most certainly are not assured.

I’m actively wondering if we are at a moment that is akin to what Bataille found in prehistory and the Upper Paleolithic cave paintings spread across Spain and France. This moment was the birth of human consciousness that begins to see itself as vaguely separated out of its surroundings, including other animals. This consciousness is born of the use of tools and the vague, contingent, and protracted realization that humans can make their environment suitable to themselves.

Consciousness, in other words, does not emerge fully formed as a clear and transparent witness to the world and its objects. This bifurcation does not immediately seek or even know clarity. No concepts, no ideas, no abstract reasoning. It just begins to separate from the vast field of experience—what Bataille calls ‘water in water’. ‘The developed tool is the nascent form of the non-I’ (Theory of Religion, 27).

In other words, utility and industriousness come first, and consciousness follows in their wake. Consciousness is the excess of this industriousness. As this excess develops, the world comes to appear as a world of things with clear definitions and boundaries. No longer ‘water in water’, human experience emerges within and from this undifferentiated intimacy as the need for more and more productivity, industriousness, and control of the surroundings, including other humans and other species, which it begins to domesticate.

Within this movement of consciousness toward clarity—what Bataille calls the ‘passage from animal to man’—we retain a ‘religious sentiment’ that is accessible to us but only if we place some value upon it. It is the capacity to broaden experience beyond the rigorous demand for clarity and to see everything as connected—spatially and temporally.

This is the experience of universality as a movement in time:

The endeavor to sum up that which separate religious possibilities have revealed, and to make their shared content the principle of human life raised to universality, seems unassailable despite its insipid results, but for anyone to whom human life is an experience to be carried as far as possible, the universal sum is necessarily that of the religious sensibility in time. (109-10, emphasis in original)

There is much to unpack in these summary lines from Bataille’s Theory of Religion (posthumously published in 1973), and I will have to write multiple essays to do so. For the moment, let’s split it into two parts. In the first part, religion is homogenized into a universal humanity that reduces all the differences of organized religions to the the same thing—the expression of an already unified humanity. This has led to ‘insipid results’ though its impulse remains ‘unassailable’.

The second part is where I’d like to spend my attention in this essay. We will mark the relationship between ‘the religious sensibility’ and its movement ‘in time’. Experience channeled through this sensibility becomes sensitive to the universal movements of time. If ‘religion’ can be reduced to a ‘what is’ definition, it is this residual and self-conscious capacity to open experience to more than the demand for clarity, knowledge, and accumulation without that openness always being driven by ‘the sleep of reason’ that posits an endless procession of hardened concepts, ideas, definitions, and truths.

Yet, we have this capacity for clarity. This is part of the human experience that should not be jettisoned. We cannot simply ‘destroy’ this clarity as if that would lead to liberation. It would only lead to a rejoining of humanity to animality—arguably what we are seeing today in the behavior of our current Republican party who threatens us with Alligator Alcatraz.

If this warlike destruction of a hard-fought moral compass is not acceptable, neither is the Tightrope Walker of Zarathustra’s Prologue who finds himself embracing the stasis of the in-between. The main text of Theory of Religion ends with a warning of this stasis of the in-between:

But the impossible thus revealed is not an equivocal position; it is the sovereign self-consciousness that, precisely, no longer turns away from itself. (111)

We should not see ‘religion’ as hovering in the ‘equivocal position’ between animality and industriousness. Bataille does not call for a new mysticism. This would be the servile morality of the slaves that turns away from itself—its body, its passions, its drives—and in doing so embraces the decadence of the Last Man who lives in a perpetual pursuit of mediocrity. This Last Man turns the danger of the Tightrope Walker into its own ephemeral entertainment.

Nor is this ‘human life raised to universality’ a Hegelian self-consciousness that would finally arrive at the clarity of an End of History and thus conclude its journey to become a thing surrounded by other things. This human life raised to universality is the movement through the passage from animal to man that keeps the final answers to the ‘what is’ questions of consciousness from desiring final conclusions.

‘Sovereign self-consciousness’ becomes the moral capacity for navigating a world incapable of final answers, but the world will go on nonetheless. The sovereign self-consciousness does not allow the dualism to completely collapse into passive or active nihilism. It is a sovereignty that says yes to our capacity to compose time while remaining open to an appreciation of experience that isn’t completely driven by the linearity of utility and industrious production.

Perhaps today, we need to read Bataille in the age of AI and social media where this duality is being reconfigured. Have we outsourced clarity of consciousness to machines while our humanity is reduced to whipped up attention, which is the excessive byproduct of our new machines? Doom scrolling and the vitality of mimetic contagion at scale are all the excessive dross of addictive algorithms designed to manufacture attention and sell it to advertisers who use other algorithms to outbid others for it in nan0seconds.

How can our moral compass survive this onslaught of motions? Has our moral compass been lost as machines take over the work of thought leaving no place for moral thought between our hijacked attention and rational machines, which provoked our excessive attention in the first place? How do we rejuvenate religion and the sacred without a new transcendence that becomes a new Gnostic turning away from the world and our problems, or a new Truth with which we dogmatize and judge others harshly?

It is from here that we must descend into what Bataille has to say about religion and apply it to our own incandescent moment.

Divinity

Humans have always used the language of religion to imbue time with sacred meaning. If one set of gods withdraws, we quickly elevate another.

When the Aztecs made regular human sacrifices, they were providing fuel to their gods in the hope that these gods would keep the Sun rising each day.

When ancient Mesopotamian court astronomers looked to the night sky, they believed the gods were sending omens—signs about future events. They maintained volumes of cuneiform tablets with the proper interpretations.

When Constantine made Christianity into the official religion of the empire, newly empowered bishops turned the ritual of Kalends into Christmas as the anchor for a new liturgical calendar. It came with a host of new feast days to overwhelm any opposing festivals, now branded as either ‘heresy’ or ‘pagan’.

Medieval Christianity built elaborate public clocks to enforce and measure this calendar. The astronomical clock at Strasbourg Cathedral (1574) included: ‘a celestial globe, calendars, a device to calculate the date of Easter, automaton figures for each day of the week, and paintings depicting Christian religious scenes, including the creation of the Universe, original sin, redemption, resurrection and the Last Judgment. An angel turned an hourglass over.’ (David Rooney, About Time, 34-5)

As Protestantism swept across Europe, they started to purchase ‘the Puritan watch’—an austere timepiece that simply guaranteed that the devout would not ‘idle away this life’ (About Time, 40).

Monasteries built the earliest water clocks to ensure the rigorous punctuality of the daily rituals known as the Divine Office. In 845 CE, a Milanese monk writes, ‘He who wishes to [observe prayer times] properly must have a horologium aquae—a water clock’ (About Time, 30).

When the Enlightenment promised open-ended progress where each generation improves upon the last, God became a ‘clockmaker’ who guaranteed that the human capacity for science and mathematical reason could decipher and manipulate His Natural Laws.

There is a progression in this movement, at least in the Western world: gods become God, who then withdraws from the drama of the world and leaves it to humans to work it out. By the time we get to Newton, God simply guarantees that the Laws of Nature are Eternal. F=MA is always true across the universe. God’s promise has become the assurance of an orderly universe intelligible to humanity’s mathematical reason.

At no point, however, does the language of religion and the positing of gods go away. God and His predecessors exist to bring order and meaning to the trajectories of time that humanity wishes to compose.

Before any of this can happen, however, humanity needs the ability to see itself and the world as having a relationship to something that can be experienced as divine. That is, it needs a consciousness that can make intellectual distinctions among the things of this world, including man, animals, and the world.

Even after Darwin, we are accustomed to seeing things as emerging fully formed. Human evolution has often been shown graphically as leaps from one fully formed species to another. Yuval Noah Harari summarizes this view in Sapiens:

It’s a common fallacy to envision these species in a straight line of descent, with Ergaster begetting Erectus, Erectus begetting Neaderthals, and the Neaderthals evolving into us. This linear model gives the mistaken impression that at any particular moment only one type of human inhabited the earth, and that all earlier species were merely older models of ourselves. (Sapiens, 8)

This clear, linear, and punctuated image of human evolution brings with it another assumption: we are accustomed to believing that at the moment Homo sapiens (‘Wise Human’) arrive on the evolutionary scene, we came ready made with reason, a consciousness, and a will to power.

Evolution doesn’t work like that. Things take a long time to become the things we think they are. Everything is dependently conditioned, to borrow Nagarjuna’s view. To understand this movement of evolutionary time in the human context, we need to imagine a time before Homo had a consciousness.

This story can be told academically, either through philosophical speculation using its native abstractions, or through anthropological means which would minimize speculation to seek hard empirical evidence.

Bataille uses both to descend into this history as he seeks the experience of this contingent birth of a human capacity for experience. This descent is religion as the capacity to blend science and speculation to open human consciousness and experience beyond the demand for clarity. But, as we’ll see, we cannot simply jettison this clarity to achieve this openness. To destroy this clarity is to collapse into animality and all manner of morally problematic conditions.

Descent into Conciousness

In Theory of Religion, among his other essays and lectures on prehistory, Bataille descends into the contingent origins of human consciousness. We have in this short book an understanding of the birth of time as something that humanity can compose. But this birth was highly improbable, slow, and contingent.

To get our bearings on this highly speculative story, we need to understand some operative concepts. I’ll lay them out as a sequence, but we’ll quickly see that the sequence is not rigorous and is mixed.

First is Bataille’s use of the metaphor ‘water in water’. Second is his use of ‘positing’ (I’m using Robert Hurley’s translation). Third is the movement from immanence to transcendence.

The three work together. ‘Water in water’ is a simile for an undifferentiated experience between human and animal. It is the condition out of which human consciousness emerges. It is ‘intimacy’ and ‘immanence’ as the original state of experience—before it can properly be called ‘experience.’ Species do not see each other as species. I think of intimacy and immanence as akin to what William James called ‘pure experience.’

How does consciousness emerge and give rise to a distinct human experience? Through the ‘positing’ action of tools. Robert Hurley’s translation regularly uses this word, and it appears to be a technical term for Bataille. We should attend to the grammatical form of this word.

Positing precedes subjectivity—a fully formed ‘I’ does not do the positing. Rather the ‘I’ of subjectivity emerges from this action of positing and does not cause it.

We must understand the sequence that Bataille is offering. Positing of a tool—a stick to dig a hole, a stone to break open a bone for marrow, a deliberately made hand axe—happens within the ‘water in water’ of the ‘intimacy’ and ‘immanence’ of existence. As this positing continues, consciousness emerges, but this consciousness is not the consciousness of a subject who could call itself an ‘I’. It is the consciousness starting to differentiate the I from intimacy and immanence:

The posting of the object, which is not given in animality, is in the human use of tools; that is, if the tools as middle terms are adapted to the intended result—if their users perfect them. Insofar as tools are developed with their end in view, consciousness posits them as objects, as interruptions in the indistinct continuity. The developed tool is the nascent form of the non-I. (Theory of Religion, 27)

Consciousness emerges as ‘interruptions in the indistinct continuity’. The interruption is the positing action that turns something encountered in the environment into a tool.

This is the opening of time as the basis for experience. In the intimacy, there is no experience of time just as there is no clarity of consciousness. All that exists is the fluidity of undifferentiated or barely differentiated motion. ‘Positing’ has the effect of Lucretius’ clinamen—a departure from a laminar and undifferentiated flow that introduces turbulence and, therefore, the possibility of experience. We can also see this as percolating time forming and crossing a threshold in which experience of a separated consciousness is becoming possible.

Transcendence

Bataille is calling out the initial movement of a nascent transcendence. We are accustomed to thinking of transcendence as accessing a ‘beyond’ that is already there.

None of this is in place yet.

We must see this nascent transcendence as a byproduct of the positing of the tool that is engendering consciousness. Transcendence from what? From intimacy and immanence; from the water in water of experience that cannot be subjective experience. This transcendence, crucially, is not yet the other-worldly divine that will become Parmenides stillness, Plato’s Forms and a Christian’s Heaven. It is not yet the hidden reality that our reason discovers behind earthly appearances.

This transcendence is better described as the opposite, but that would be too simple. Transcendence is simply the excessive byproduct of the positing action of a nascent consciousness that is beginning to experience its ability to make and use tools. As humanity experiences some capacity to shaped its surroundings, those surroundings begin to appear external to that consciousness. He describes this transcendence as provisional and inconclusive (73). It will take time before this transcendence becomes the permanent, other-world home of Eternity and the locus of meaning.

This is the contingent and difficult birth of a transcendent place where we will eventually place our measures of reality—Hesiod’s Theogony, Plato’s Forms, the Gnostic’s Pleroma, Plotinus’ One, Augustine’s Eternity. We will use myth to shepherd them into the transcendent home we’ve created for them. But, in the meantime, the divine remains close by in the immanent water-in-water that has not yet separated into the realms of Heaven and Earth.

Archaic religion will be the experience of collapsing, if only momentarily, the transcendent back into the immanent.

The divine was initially grasped in terms of intimacy (of violence, of the scream, of being in eruption, blind and unintelligible, of the dark and malefic sacred); if it was transcendent, this was in a provisional way, for man who acted in the real order but was ritually restored to the intimate order. (73)

Bataille is describing something that has not yet happened. He is attempting to capture something happening before it hardens into an essence, before it becomes all the familiar ways of thinking of ourselves and the world that we take for granted. He is describing ‘a sudden movement of transcendence’ that became, though not necessarily, the transparent consciousness that we take for granted.

Passage

He is describing a passage that could be understood as ‘a wheel rolling out of itself’ to borrow a phrase from Nietzsche’s Zarathustra. Neither purely linear nor purely circular, these movements are messy, and we shouldn’t try to schematize them at the risk of losing the experiential narrative he is seeking to unfold.

The moment of change is given in a passage: the intelligible sphere is revealed in a transport, in a sudden movement of transcendence, where tangible matter is surpassed. The intellect or the concept, situated outside time, is defined as a sovereign order, to which the world of things is subordinated, just as it subordinated the gods to mythology. In this way the intelligible world has the appearance of the divine. (Theory of Religion, 73)

We should attend to the grammar of Hurley’s translation. The first sentence is movement and change and transport. All verbs situate us in the present, and we are placed in the contingency of these motions as they are happening. The verbs of the following sentences are all past tense. All the movements of the first sentence have been sorted and hardened into things, and we are looking back on a done deed.

The ability to push and pull us through this threshold is Bataille’s narrative power. This is not an act of knowledge transmission. It is ‘an act of consciousness, while carrying one’s elucidation to the limit of immediate possibilities, not to seek a definitive state that will never be granted’ (Theory of Religion, 12). In other words, he seeks to unfold a narrative about the birth of consciousness as a way of not merely undoing what it has become—that would be mere deconstruction—but of shepherding the consciousness of the writer and the reader back across a threshold where consciousness itself was experienced more intimately as a passage, a transport, a movement not yet settled into a demand for clarity.

Passage from Animal to Man

All of this contingent and tubulent motion out of undifferentiated intimacy and immanence (the water in water) yields a ‘passage from animal to man’, which is crucial for understanding Bataille’s notion of time and experience.

To makes sense of Bataille’s notion of time, we have to understand ‘passage’ as not just a linear movement from Homo faber (toolmaker) to Homo sapiens by way of the Vérèze Valley’s Lascaux caves. This passage remains available as eroticism, violence, the excess of consumption, the sacred, and transgression—not just passive historical knowledge. We can, in other words, experience this passage, but not in its purity.

We can go further. Experience itself is the eternal recurrence of ‘the passage from animal to man’. Time opens up the moment we become aware of the power of our ‘industriousness’ to change the world around us to suit our needs. At that moment, we begin to experience time as stretched by the action of purpose—i.e., industriousness. That momentary, inconclusive, and provisional transcendence is a byproduct of the tools that reveal to the human that he has a capacity for industriousness—the ability to shape his environment to suit his needs.

This revelation does not come all at once. To say it again, it is a provisional transcendence that is inconclusive and temporary. It has not yet hardened into the ‘dualism’ of heaven and earth, good and evil, is and ought, appearance and reality, present and future, subject and object.

Dualism, Mediation

The dualistic consciousness only sees things, but these things are split into two—appearance and reality, material existence and purpose. This includes the self because the I and the you are also things.

In one sense, the dualist’s world is complete, finished. All the truths are established and anything that appears to be new is an illusion. Reality remains hidden away waiting for reason to discover and to communicate. In another sense, the world is moving according to a trajectory, from appearance to reality, from existence to fulfillment of purpose.

The dualist has no need for God because His work is done. All that remains is for the human work of rationality to put time to work as utility, productivity, purpose with occasional transgressions and reconnections with the intimacy.

The divinity will become a thing—an optional thing—and we will sacrifice the thing so as to bring full ‘authority and authenticity’ to the world of industrious production:

Authority and authenticity are entirely on the side of things, of production and consciousness of the thing produced. All the rest is vanity and confusion. (Theory of Religion, 97)

This is the birth of Cartesian science—the reduction of consciousness to the apprehension of the natural light of reason completely disconnected from any confused intimacy. Dualism is no longer in need of a mediation that forms a bridge between this world and the fully external other world.

The intimate order is not reached if it is not elevated to the authenticity and authority of the real world and real humanity. This implies, as a matter of fact, the replacement of compromises by a bringing of its contents to light in the domain of clear and autonomous consciousness that science has organized. (Theory of Religion, 97)

While Bataille does not mention Descartes, he is clearly the figure for this ‘replacement of compromises’ between the inmate and our consciousness. If archaic religion mediated between a nascent consciousness (learning of its industrious power to shape its world) and the intimate order of animality (as the water in water that it momentarily transcends), the Cartesian consciousness seeks to do away with this compromise by turning all of experience into the potential for clarity—everything becomes a thing that can be clearly and distinctly known, including God.

Time and Tightropes

And here we arrive at the problem of time for Bataille. The order of intimacy and animality has a fundamentally different temporality than the order of clarity and things. The one is instant and consumed completely in its moment of experience while the other is prolonged as it stretches experience in time in an endless pursuit of redemption through commodity production and wealth accumulation:

The difficulty of making distinct knowledge and the intimate order coincide is due to their contrary modes of existence in time. Divine life is immediate, whereas knowledge is an operation that requires suspension and waiting. (98)

For Bataille, like Nietzsche, it may be that humanity cannot live morally without duality. We find ourselves strung on a tightrope between these ‘contrary modes of existence in time’.

On the one hand, we can’t go back to the animality of immanence if we wish to come to terms with violence. Morality cannot be a regression to a lost past. How could this even be achieved without taking the form of unhinged violence and war against our own consciousness?

On the other, we can’t simply live within the ‘suspension and waiting’ of a time that never moves forward. Again, this is the lesson of the Tightrope Walker in Zarathustra’s Prologue—he is stuck between towers as an entertainer for the herd of Last Men below. His existence has become fragile, so much so that the interruption of a dwarf causes his demise.

Sovereign Self-Consciousness

Bataille turns to the phrase ‘sovereign self-consciousness’ to preserve a moral compass that does not seek one tower or the other, nor does it seek the fragile stasis of the permanent in-between.

Being and becoming are not helpful terms for seeking clarity in Bataille’s moral vision. This sovereign self-consciousness is the deliberate act of embracing all of experience and all of time as a ‘universal humanity’:

And if we raise ourselves personally to the highest degree of clear consciousness, it is no longer the servile thing in us, but rather the sovereign whose presence in the world, from head to foot, from animality to science and from the archaic tool to the non-sense of poetry, is that over universal humanity. (Theory of Religion, 110)

In this way ‘the whole of human experience is restored to us’, and this is what Bataille means by his theory of religion—the capacity for experience to take in all of the human adventure, ‘from animality to science and from the archaic tool to the non-sense of poetry.’

We are back to the combination of the philosophical and the anthropological, in which the power of combination is that of religion. The one is informed by the other, and when they are combined in the interest of pushing human experience beyond its tyrannical demand for clarity, we are in the ‘sensibility of religion’. We are not outside of sciences and philosophy, not outside of useful tools and poetic non-sense, not outside intimacy and clarity.

We have not transcended any of this, but we have absorbed it into our experience. We are in the universal humanity that accepts it all as experience: ‘It implies SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS taking up the lamp that science has made to illuminate objects and directing it toward intimacy’ (Theory of Religion, 97).

Time as Practice

How does this work as a practical matter of our own experience? It’s not that difficult to understand.

Sitting in his room, Bataille looks around and sees ‘the clear and distinct meaning of the objects that surround me’ (101). He immediately temporalizes these objects so as to see them in a field of coalesced motions. He starts by descending into the industrious labor necessary to make the entire scene possible:

Here is my table, my chair, my bed. They are here as a result of labor. In order to make them and install them in my room it was necessary to forego the interest of the moment. As a matter of fact, I myself had to work to pay for them, that is, in theory, I had to compensate for the labor of the workers who made them or transported them, with a piece of labor just as useful as theirs. (101)

The chain continues as Bataille untangles the web of productive labor to encompass ‘the work of the butcher, the baker, and the farmer who will ensure my survival and the continuation of my work.’ It’s all positively parasitic, to use Serres’ vision.

But then another action enters that cannot be reducible to the productive web of sequences. ‘Now I place a glass of alcohol on my table.’ Yes, he has been productive in trading his labor for the table and the glass and the alcohol. But this table is no longer a ‘means of labor: it helps me to drink alcohol’—i.e., consumption for consumption’s sake, purely unproductive (102).

The web of sequences of production gives way to consumption as destruction of the endless progression of useful industriousness, if only momentarily. This is not a defect of the system, but its byproduct—just as pollution is the byproduct of production.

This is one way to move one’s perception from seeing things to experiencing duration. Bataille expands the present things into an infinite web of conditions that make his room and his work possible while also making waste and useless excess equally a part of the movements: ‘The immediate negation diverts the operation toward things and toward the domain of duration’ (99). That is, a different experience of time becomes possible when we begin to see the movement of productive time at its limits—’the point at which the excess production will flow like a river to the outside’ (103).

If this happens ‘without the least consciousness’, we risk dehumanizing this excess, and its destruction will be indiscernible from war. Attention must remain self-conscious if it is to retain a sovereign moral compass rather than either a servile one or destroy the moral compass altogether.

Lascaux

Let us finish this effort by descending from this present scene into prehistory—into the well of the Lascaux caves.

To encounter the well of Lascaux is to encounter the linearity of ‘the passage from animal to man’. In that encounter we have some access to it—the passage becomes contemporary experience. We encounter the prehistory of humanity before it was fully experientially and conceptually separated from animality.

To be sure, Bataille’s reading is not uncontroversial or definitive. While others see ritualistic depictions designed to bring about successful hunting, Bataille sees the birth of a moral consciousness where the killing of a sacred animal requires atonement. In the bird-man, he sees this atonement—the need to sacrifice a human for a transgression against an animality that is beginning to appear as the embodiment of the sacred.

There is, admittedly, something odd about trying to ‘interpret’ cave paintings. Interpretation, as a concept, carries with it assumptions about subjects, objects, and meaning making that Bataille is trying to complicate. To ask, ‘What do these cave paintings mean?’ is to engage in historical anomaly. We impose the fully formed clear consciousness on a moment in human history where, according to Bataille, it was still being worked out.

In this sense, the paintings are part of this historical record, but not in a representational sense. To encounter the paintings is to encounter ourselves in an earlier state where subjects, objects, and meaning making is not yet given. This encounter cannot, however, be done without a deep engagement with anthropology and philosophy. When done with the intent of finding a universal humanity, such an experience is religious for Bataille. The ‘religious sensibility’ makes the connection between experience, philosophical speculation, and anthropological knowledge in such a way that our precious certainties—I and me, you and it—loosen their grip on our consciousness. We begin to understand and to experience the possibility that we are woven into the cosmos not as a special transparent consciousness, but as part of the whole moving in the contingency of time.

The earliest prehistoric art surely marks the passage from animal to man . . . Prehistoric art is therefore the only path by which the passage from animal to man became, at this distance, tangible for us. (The Cradle of Humanity, 58, Kendall and Kendall trans.)

In the essay ‘Prehistoric Religion’ he captures the long arch of this passage beautifully:

Specifically, the apparition of the animal was not, to the man who astonished himself by making it appear, the apparition of a definable object, like the apparition in our day of beef at the butcher that we cut up and weigh. That which appeared had at first a significance that was scarcely accessible, beyond what could have been defined. Precisely this equivocal, indefinable meaning was religious. (The Cradle of Humanity, 135).

We live in the long shadow of this passage where the cave painting of the animal that astonishes has transformed into the mundane presentation of butchered meat behind a glass case. This passage from animal to man, which has continued for thousands of years, has turned religion from a genuine experience of limits into ‘an experience that limits it, that even contradicts it: the allegiance to a particular religion’ (139).

As human consciousness has driven our capacity for experience into the relentless march of clarity and utility, we have absorbed the religious sensibility into this composition of time. Yet, as we’ve seen, we cannot do without this clarity of consciousness if we are to retain some human moral capacity. Without linear time that projects a better and more abundant future, we give up on progress altogether. Without religion—our willingness to engage with the experiential and moral limits of this consciousness—we risk this linearity becoming tyrannical.

To descend into the shaft at Lascaux is to descend into the long and contingent branching and bifurcation when human consciousness was using art to separate itself from animality, but in doing so it was developing a moral compass that could retain the ambivalence and equivocality of this separation.