Reading The Incandescent: Human Scale and Accursed Shares

How the speed and scale of human activity requires a new understanding of ethics, morality, and politics as outlined in Michel Serres The Incandescent

Summary: This essay uses Serres’s figures of scale, measure, and the “accursed share” to explore how ethical life is situated at the intersection of human limits and unbounded systems. It reads Serres’s incandescent insight through questions of magnitude and consequence, asking how we can think responsibly about action when human scale collides with complexity beyond our immediate control.

This essay is part of my series on the work of Michel Serres.

Speed and Scale

In the previous essay in this series on Reading le Grand Récit, I discussed the central moral question around which these later works of Michel Serres revolve. It is deceptively simple:

How can we free vital energy from aggression without allowing the former to fall back into the latter? This is the foundation of morality filtering life from death.’ (149)

What makes this question newly urgent is not a change in human nature, but a change in scale. Human nature operates on a global scale.

For most of human history, moral life unfolded within worlds small enough for actions to remain roughly proportionate to their effects. Ethical practices—rituals of restraint, norms of reciprocity, techniques of self-command—developed in villages, clans, and tightly bounded communities. These practices worked not because they eliminated excess, but because they could dissipate it locally. Surplus energy found outlets. Violence could be deflected before it spread.

Nothing in The Incandescent suggests that these inherited moralities should be discarded. On the contrary, they are indispensable. They remain among humanity’s most reliable means of preventing aggression from taking hold at close range. They shape selves capable of restraint, judgment, and care.

As I’ve written before, the Stoic practice of assent—the capacity to delay the automatic movement from impression to action—is a genuine discovery that remains universally true and relevant.

The difficulty arises when these same practices are asked to operate far beyond the conditions under which they were formed.

Human actions now spread well beyond the purely local. Ordinary gestures—purchasing, consuming, disposing—repeat millions of times at industrial speed. Their consequences accumulate across distances and durations no individual can directly perceive.

What once dissipated locally now aggregates globally, even as we continue to experience our actions as small and contained.

Consider the plastic water bottle. Used once and discarded without thought, it appears morally negligible. No harm is intended. No damage is immediately visible. Yet multiplied across millions of people, across days and years, the bottle becomes a world-object: circulating through oceans, breaking down into microplastics, entering food chains and atmospheres.

What matters now is not the single gesture, but repetition at a scale our perception cannot easily fathom.

Serres captures this shift with a simple thought experiment. Six people picnicking on a beach can clean up after themselves. Responsibility remains legible. The scene is reversible. Ten thousand people performing the same ordinary acts leave behind a transformed shoreline. Nothing essential has changed in behavior; scale alone has changed the situation. The everyday becomes irreversible. (159)

Scale turns the everyday into something larger and irreversible.

This is the threshold we have crossed, and it locates our moral problem. The action itself has not become more vicious. Intention has not suddenly soured. What has changed is that surplus energy can no longer be absorbed where it is produced.

Excess no longer bleeds off through familiar ethical channels. It circulates.

The Incandescent begins from this problem of scale. Its question is not how to invent a new moral system, nor how to moralize planetary harm after the fact. It asks instead whether experience itself can be stretched—whether we can learn to feel the consequences of scale strongly enough that moral orientation becomes possible again.

What emerges is not a rupture or a new moral system, but a rejuvenation of inherited moralities—Stoic, Epicurean, Christian—stretched just enough to meet the scale of the world we have made.

Pollution as accursed share at scale: ‘Six campers can live three days on a beach without any offense; ten thousand people turn it into a cesspool; sacking the planet, tourism changes sites of beauty into sewage fields’ (The Incandescent, 159)

This engagement with human scale and consequence extends the themes of L’Incandescent, where emergence and unpredictability foreground moral attention.

Accursed Shares and Thermodynamics

The problem Serres names is not simply that human action has grown large. It is that excess now accumulates faster than it can be dissipated.

In small worlds, surplus energy—material, social, affective—found outlets. It could be spent in ritual, absorbed by community norms, redirected through restraint, or discharged through repair and repairable harm. Even violence, when it occurred, remained legible and bounded. Moral life functioned as a series of filters, preventing excess from hardening into destruction.

At planetary scale, those filters no longer operate with the same experiential immediacy.

What Serres takes from Georges Bataille’s notion of the accursed share is not its fascination with sacrifice or transgression—’the modern subject, from Sade to Bataille, who delights in destruction’ (139). He retains instead its most basic insight: excess is inevitable. Every system that produces energy throws off surplus. The question is never whether there will be an accursed share, but how, where, and at what scale it accumulates. ‘Changing scales imposes the accursed percentages particular to large numbers… That said, let’s bring the accursed portion down to the minimum’ (159–60).

What changes under modern conditions is not the existence of excess, but its mode of circulation. When ordinary actions repeat at industrial speed, surplus no longer appears as an exceptional remainder. It becomes structural. Pollution, waste, ecological degradation, and diffuse forms of violence emerge not from singular acts of aggression, but from the amplification of the everyday.

This is why original intent recedes as a reliable moral and ethical guide. The individual who discards a bottle, books a flight, or clicks “purchase” does not will the resulting harm. Yet harm occurs nonetheless, distributed across systems and delayed in time. Responsibility does not vanish—but it is displaced, stretched thin across networks no single actor can fully see or govern.

Here aggression enters Serres’s account in a new register. It is no longer primarily psychological or interpersonal. It is thermodynamic. When surplus energy cannot be absorbed or redirected, it returns as destruction—not because anyone chooses it, but because nothing stops it.

‘Ineliminable? I believe so,’ Serres writes. ‘This accursed portion strongly resembles that sum of violence I compared earlier to the energy constant in a physical system. Might there exist then a kind of dynamic first principle in collectives? I don’t know, but I do think so’ (159).

This is a crucial move. Serres is not calling for the end of violence—for that would only engender more violence, more scapegoats, more heroic exceptions. ‘We remain drugged by myths demanding blood and death for an exception’ (143).

Thermodynamics displaces the scapegoat. The accursed share no longer calls for a villain, but points us to the collective effects of speed and scale themselves. No one can be blamed—yet we are not absolved. We face a shared reality thrown off by the thermodynamics of our computable, networked existence.

Seen this way, the accursed share is not an argument for moral resignation, nor a call for Epicurean withdrawal into a permanent Garden. It is a diagnostic. It tells us that ethical life today cannot aim at purity or total control. It must instead learn to intercept surplus early, close to where it is generated, before it hardens into irreversible harm.

Accursed shares are ineliminable at scale—but they can be minimized, without requiring us to manufacture new scapegoats for our collective thermodynamics.

Pan and the Extension of Moral Experience

The problem confronted in The Incandescent does not require a new moral system. It requires a widening of experience. The inherited practices of morality—Stoic restraint, Epicurean limits, Christian refusals of violence—remain fundamentally sound. What has changed is the scale at which their consequences unfold. Moral life has not become obsolete; it has become underscaled.

The task, then, is not to rethink morality from the ground up, but to extend the scope of what moral experience can register. Human action now operates through globally distributed, computationally accelerated systems whose effects far exceed what any individual can directly perceive. Yet the point at which energy is first intercepted—where impulse either escalates or dissipates—remains stubbornly local.

Moral experience always runs through the individual.

This is where The Incandescent introduces the figures of Pan. Pan is not a new ethical authority, nor a metaphysical claim about totality. He is a figure for the extension of individual experience: a way of stretching moral attention beyond the interpersonal without abandoning the practices on which morality has always depended. Panchrone, Pantope, Pangloss, Panurge—each presses against a different limit of experience, not to reach Plotinus’ One or Parmenides’ stillness, but to prevent moral perception from collapsing back into the merely local.

Crucially, this extension does not bypass impulse control; it doubles down on it. Moral life, for Serres, still turns on the capacity to interrupt automatic escalation—to refuse the immediate conversion of excess into violence. What changes is that this refusal now matters at scales the individual cannot fully see.

Pan is not, therefore, a new totality; these figures are not rising above the fray to see all the consequences of our actions. This would be to willfully miss Serres’ point about the importance of time—Panchrone is the most difficult and important of the Pan figures—and how moral experience happens through the individual:

I can refuse to avenge myself. I can refuse violence. I this respect, violence depends on me. Collectively, it doesn’t depend on me, nor specifically … I can burn within myself this violence, the refuse and discharge of the cesspool; I can, next, invite my neighbor … I invite you, you to whom I don’t return any brutality, to the same operation… (162)

Nothing here resembles withdrawal or moral pride. Though Serres draws on Stoic and Christian practices of self-control, they operate here under the pressure of Pan—not as private virtue, but as globally extended moral experience. The refusal to escalate does not resolve violence once and for all; it interrupts its automatic amplification without knowing how or if it will spread.

This is “moral experience, as a non-violent and measured relationship to evil” (165). Violence may be produced collectively, but its energy must pass through individuals who can dissipate its force.

John’s Jesus stages this interruption with clarity, and Serres uses this episode as the prologue to Religion. A crowd’s gathering energy, directed toward an adulterous woman, is reversed with a single demand: “Let the one without sin [anamartetos] cast the first stone” (John 8:7). The flow of violence is turned back into personal contemplation. No stone can be cast. The mimetic contagion stalls before it can catalyze into a scapegoating event.

What happens to the energy?

The refusal to escalate does not eliminate violence—locally or globally. It prevents its automatic consolidation. Energy burned off here does not vanish; it propagates differently, spreading as contagious restraint rather than concentrated harm.

Pan’s role is to keep this local act from shrinking back into insignificance. He casts a shadow over experience, reminding us that the refusal enacted here participates in effects that extend far beyond it. Moral experience is thus neither totalized nor privatized. It is stretched—just enough—to remain oriented in a world where action outruns perception.

Seen this way, Serres does not abandon ancient moralities. He subjects them to pressure. He asks whether practices forged for small worlds can still function when humanity’s computational and technological reach has become planetary. His answer is not a new code, but a renewed discipline of attention: returning to the individual as the site where excess can still be intercepted, even as its consequences now propagate globally.

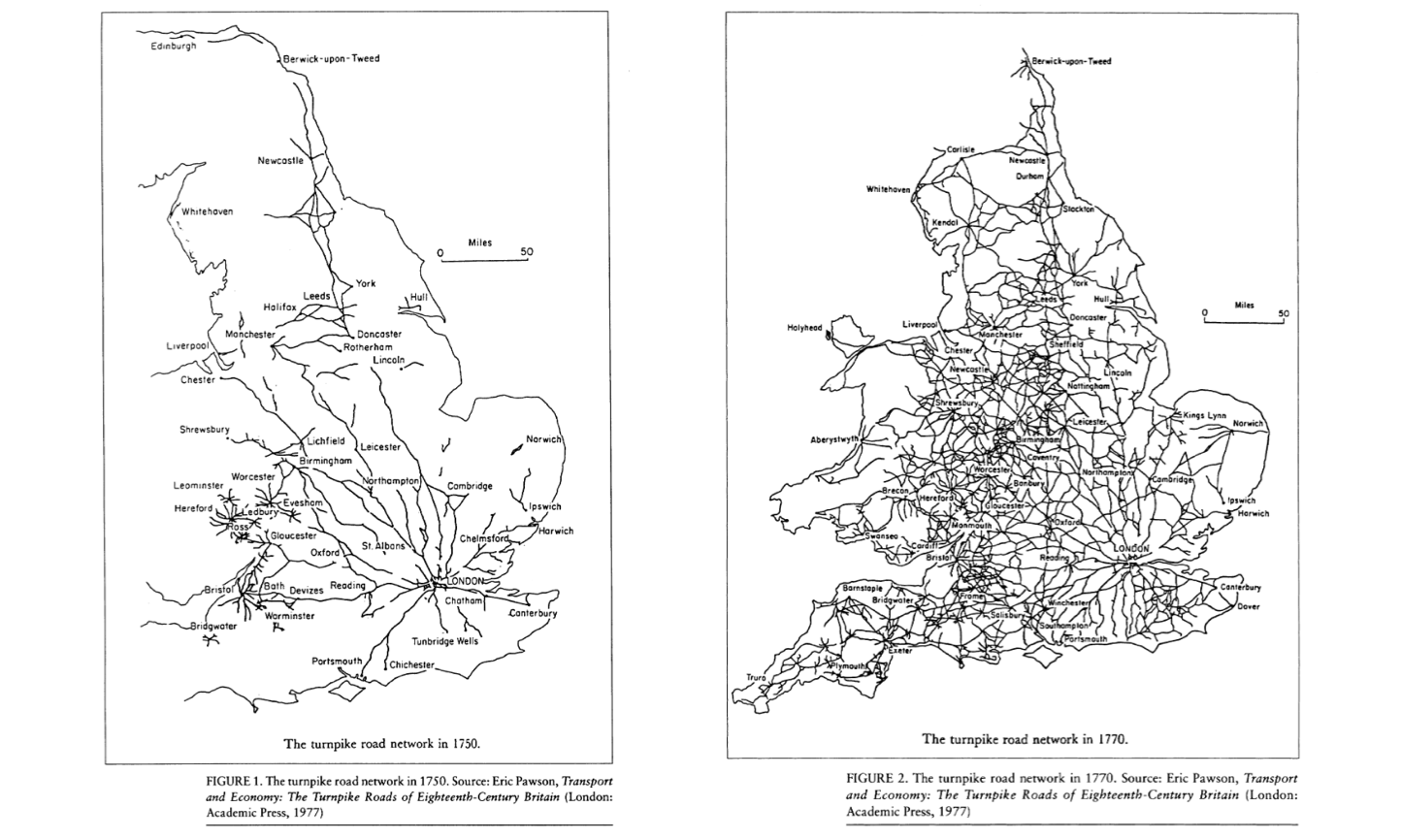

The British Enlightenment builds roads at an unprecedented speed and scale to transform the island into a networked economy.

Our computational power now covers the globe. We are a world-object.

Such questions of human measure resonate with broader explorations in Finding Purpose in a Computational World, where moral orientation must adapt to environments that exceed traditional scales.

Dissipation, Rejuvenation, and the Limits of Politics

The Incandescent does not ultimately offer a reform program or a blueprint for governance at planetary scale. Serres is clear-eyed about the limits of politics when action moves faster than institutions can respond. Law, policy, and regulation matter—but they arrive late.

Politics and law are downstream from culture, and culture is downstream from experience.

This is why Serres refuses both despair and utopia. He does not imagine that global systems can be mastered, nor that violence can be eliminated. Accursed shares are ineliminable at scale. Excess will always be produced. The question is not how to end this condition, but how to live within it without allowing surplus to collapse automatically into destruction.

The answer he gives is modest, almost disarming: dissipation begins locally, and it propagates gradually. Moral force does not scale by command. It spreads by contagion. A refusal here interrupts an escalation there. Energy burned off in one encounter does not vanish; it alters the conditions of the next.

This is why moral experience, even under planetary conditions, must return to the individual—not as hero, not as sovereign, and not as scapegoat, but as a site of interception.

The only energies we can reliably govern are the ones that pass through us.

In this sense, Serres’s thought is quietly radical but powerfully simple. He rejects the fantasy that salvation will arrive through total coordination, just as firmly as he rejects the fantasy that private virtue alone is enough. What he offers instead is a practice of rejuvenation: the renewal of inherited moral disciplines under new pressures, stretched just far enough to remain operative in a world defined by speed and scale.

Rejuvenation is not balance. It is not equilibrium. It is motion—continuous adjustment under changing conditions. Stoic restraint, Epicurean limits, Christian refusals of violence do not disappear; they are reactivated as techniques for living amid systems that cannot be fully seen or controlled. They become ways of keeping moral attention alive when consequence outruns comprehension.

Politics, if it is to have any future at planetary scale, can only emerge from this ground. Not from purity. Not from total vision. But from countless acts of measured refusal that prevent violence from consolidating, scapegoats from forming, and excess from hardening into inevitability.

Serres leaves us, finally, not with solutions, but with orientation. Moral life does not end when scale overwhelms perception. It begins again—underscaled, fragile, and necessary—wherever violence is refused, energy is dissipated, and the next neighbor is invited into the same operation.

That, for Serres, is what it means to keep life from falling back into death.