The Discovery of Time - Stephen Toulmin and June Goodfield

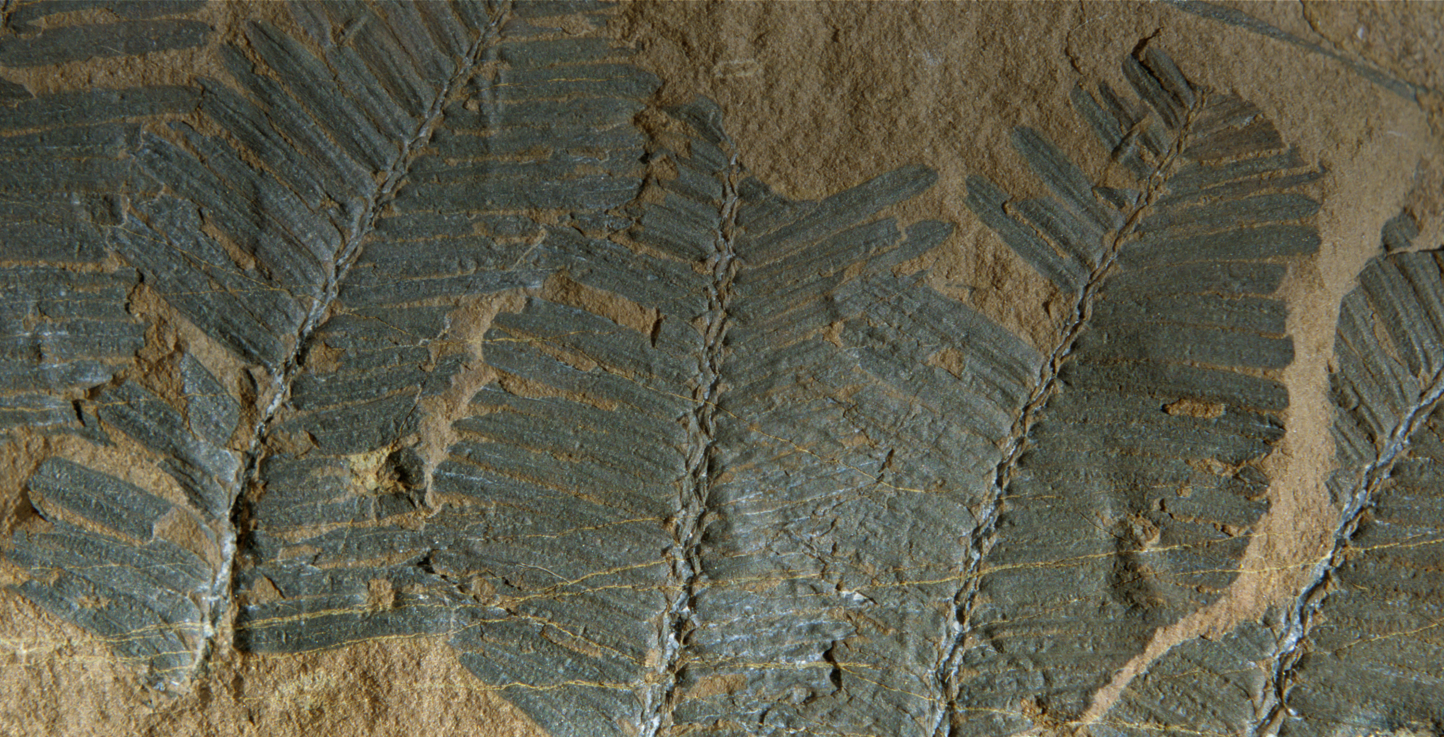

Enlightenment geologists and zoologists did the hard work of showing us that the Earth must have existed much longer than Biblical reckonings of 6000 years. Image credit: Keith Douglas

Living in Time

When Homo sapiens arrived on the scene, we did not automatically come with an understanding of time that stretches infinitely far into the past or into an indefinite future. This consciousness needs to be crafted, shaped, created. It therefore has a history—a very recent history in fact.

The latest rethinking of time by theoretical physicists like Sara Walker, Lee Smolin, Carlo Rovelli et alia is not an ex nihilio act of genius. It is part of a much longer history that Toulmin and Goodfield trace in The Discovery of Time. In short: for our latest rethinking of time to become possible, humanity had to first discover time as something other than a dimension of space or something controlled by Christianity’s God.

Reading The Discovery of Time is to realize that perhaps the Enlightenment’s greatest legacy is to have situated the human condition within an infinitely stretched duration. This changes our capacity for experience profoundly, and it is part of Nietzsche’s articulation of the Death of God—not an instantaneous event, but one that takes centuries and has profound effects for how we understand, experience, and compose time.

The 6000 Year Time-Barrier

Only 300 years ago, the common understanding of how long God’s creation had existed was about 6000 years. If Homo sapiens has been around for 150,000 years or more, then our discovery of an elongated time occurs within a tiny fraction of our existence as a species—.2% to be precise.

Toulmin and Goodfields’s 1965 book The Discovery of Time tells the story of how humanity discovered, during the Enlightenment, that the Earth and its inhabitants have a much greater duration than 6000 years.

The story told in The Discovery of Time is just that—a discovery that forces itself on humanity over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries because elongated time provides a better explanation for what geologists were finding out about the age of the Earth.

But scientific inquiry has established, and come to terms with, the enormous extent of past time only very recently. And in the last two and a half centuries, during which the accepted time-scale has expanded from six thousand years to six billion, men have been obliged to rethink their beliefs, so as to fit them into this new time-perspective. The gradual erosion of long-cherished ideas and convictions accompanying this transformation will be one of our chief concerns in the present book. (20)

This is a story about crucially important changes in the capacity for human experience directly related to how we become conscious of how long the Earth has been around.

God is pushed to the sidelines as His grand narrative begins to look like a woefully incomplete account of time.

Christian Time

Christianity gave the world a consciousness of time that is punctuated as ‘a sequence of unique events, each of which broke abruptly with what came before.’ This is not ‘the slow unfolding of a continuous development’ (56).

Thus, Christianity gives humanity an understanding of history that is meaningful for humans. ‘The resulting conviction, that the course of historical events had a profound significance, was the most important single legacy passed on by Judaism to Christianity’ and by extension it ‘helped to shape the whole European tradition’ (56).

But we should not, as is customary, see this as a narrative of progress. History is headed toward and end, but there is no requirement that the flow of time yield an incrementally improving condition for humans. In fact, much of the Middle Ages saw the necessary decay that many believed was an indication that the end of time was near:

By A.D. 1500, the Decay of Nature had almost reached its limit. Taking 4000 B.C. as the date of Creation, Luther calculated that men were already in the sixth and last age of unveil history—the Age of the Pope…. ‘The world will perish shortly,’ he declared: ‘The last day is at the door, and I believe the world will not endure a hundred years.’ (76)

God sets time in motion—from Genesis to Apocalypse—and is under no obligation to make time into the steady march of an improving human condition. More than that, as an omnipotent power, he certainly is under no obligation to make time the steady and measurable motion of the heavens or the unfolding of natural causes and effects.

This legacy is powerful. Once this grand narrative is in place, it is very difficult to jettison without nihilistic consequences. The elongation of time will play a central role in the Death of God if only because believing that the march of time should have a purpose is compelling, even if humanity is not in charge of the purpose.

Looking to the future, Christian time was oriented to its imminent end. But this had been going on for an exceptionally long time by Biblical standards. We are accustomed, as a result, to see the unraveling of this Biblical history as a natural development: the longer the delay, the more untenable the grand narrative becomes. The Death of God appears to be a kind of withering away.

For Toulmin and Goodfield, however, the importance of Christian time is less about the end of time than its beginning and the grip that 4000 BCE had on intellectual work and human experience prior to the Enlightenment:

All that could be known about the remote past of the cosmos was contained in the sacred chronicles of the Bible, and men in A.D. 1300 were as far as ever from reasoning their way past the historical time-barrier. (70)

Reason itself has to be stretched in such a way that experience opens to a sense of time that is not contained by historical texts. Rather, better explanations start to emerge about rock stratifications, and those explanations necessitate new ways of seeing time that are incompatible with the 6000 year consensus.

A Slow Turning

What we have is a relatively slow unraveling of threads that painstakingly break down the 6000-year ‘time-barrier’.

The core story is the passage through an impasse in how humans attend to their surroundings. What arises from this mode of attention are some of the Enlightenment’s most important legacies.

First, extended time, which is the substance of Toulmin’s and Goodfield’s narrative: ‘how men acquired a sense of history, and realized the extent of past time’ (142). Second, the commitment to better explanations (to use David Deutsch’s characterization of the Enlightenment) as the route to a better human future.

Third, these explanations stretch our consciousness of time beyond the multi-generational transmission of memories and traditions. The Bible itself is such a text—the dominant one for the North Atlantic world. Looking beyond its presumed 6000 year time-frame could only happen when human experience is stretched by compelling explanations and arguments.

It is one thing to recognize the changes and chances of an individual human life—lived on the unchanging stage of the Earth, against the immutable backcloth of the Heavens. But to acknowledge the mutability of the Earth, the living creatures upon it, and even the great Heavens themselves, is something men could do only under the pressure of compelling arguments. (21)

Fourth and perhaps most important, explanations and arguments by themselves do not compel anyone to accept a truth. Better explanations and arguments do not naturally and organically win out. If we rely only on the words ‘explanations’ and ‘arguments’ as if they are ahistorical modes of human experience that have a special relationship to truth, we miss the vitality of this massive expansion of the capacity for human experience.

We have to add some other ingredients to find out how explanations and arguments break the 6000 year consensus.

From Natural Laws to Causal Sequences

Core to the story that Toulmin and Goodfield tell is how some forms of knowledge remain ‘unhistorical’. From the ancient Greeks through Newton, what it means to know anything for certain is to remove time to focus on fixed rules or laws. The designation ‘historical’ and ‘unhistorical’ are technical terms in this work.

Natural laws go from being the output of God who created a fixed Natural Order to temporalized processes that can be calculated backwards and forwards. We can also think of this as the movement from vertical laws connecting everything below up to God to horizontal laws that make the movement of time and change calculable.

This is a slow turning that is also an unraveling. The vertical does not suddenly topple over to become horizontal. The Enlightenment will struggle to effect this somersault in the order of time. Geologists like Buffon and Cuvier, in very different ways, will continue to try to read the events and timeline of Genesis in stratified rocks. Today we look backward and see them as confused, but history must be lived forward with the intellectual and experiential scaffolding available at the moment.

A coherent story can only be told when looking backward.

For Toulmin and Goodfield, the nascent social sciences do not do the hard work of turning, but the natural sciences do—geology in particular.

…the first branch of natural science to become genuinely historical was geology: the crucial battle between scriptural chronology, based on human traditions, and natural chronology based on ‘the testimony of things’, was fought out over the history of the Earth. If our ideas of the past are now no longer restricted within the time-barrier of earlier ages, this is due above all to the patience, industry and originality of those men who, between 1750 and 1850, created a new and vastly extended time-scale, anchored in the rock strata and fossils of the Earth’s crust. (141)

To look at the composition of the Earth and to ask how long it would take for all of this to happen is to automatically complicate Biblical authority over our experience of time. It’s not just that the 6000 year consensus appears to be wrong; it’s that the composition of time itself is out of joint with the punctuated linearity of the Bible’s grand narrative.

Finding Time in the Landscape

Geologists broke the 6000 year time-barrier by staring into the landscape to find the accumulation of time. Most importantly, time gains a power of its own as the cumulated effects of processes in motion. James Hutton, writing in 1788, captures this sentiment:

Though, in generalizing the operations of nature, we have arrived at those great events, which, at first sight, may fill the mind with wonder and with doubt, we are not to suppose, that there is any violent exertion of power, such as is required in order to produce a great event in little time; in nature, we find no deficiency in respect of time, nor any limitation with regard to power. But time is not made to flow in vain; nor does there ever appear the exertion superfluous to power, or the manifestation of design, not calculated in wisdom to effect some general end. (156)

We find in this remarkably clear expression the somersaulting necessary to turn Christian time into elongated, natural time. Time does work because it has no ‘limitation with regard to power’. But it moves slowly and methodically and has no inherent need ‘to produce a great event in little time’.

While this vision of time may lead to ‘wonder and doubt’, it is providential in its motions. Hutton was not writing an atheist’s manifesto. His reconciliation of Christianity with the facts of geological time was not appreciated by his peers, and he came under attack for heresy.

Nonetheless, we find humanity existing amid the ‘operations of nature’ unfolding slowly, methodically, wondrously beyond our ability to experience them. Yet, these slow and methodical operations of nature are ‘calculated in wisdom to effect some general end.’ Here ‘calculated’ fits Dr. Johnson’s third definition: ‘To adjust; to project for any certain end’. But it is God who is doing the calculating—God has ensured a calculable progression of nature just as he had done for Newton.

In this quote from Hutton, we are witnessing the somersaulting of time from the pure Biblical punctuated linearity to the calculable progression of causal processes. God is not pushed aside so much as He changes His role: He becomes the guarantor of calculability and the steady unfolding of natural processes.

This is not anywhere to be found in the Bible.

Hutton is not completely a Newtonian. He does not look at the world around him and see equations. He sees change unfolding over very long periods of time. He assumes this change is calculated by God toward providential ends, but that does not mean that the calculations are mathematically interpretable. All that ‘calculated’ means is that God has designed these processes toward an end, but the end itself is no longer at the end of time. Time itself is orderly, and every step in its powerful movement, though minute, is providential.

WHEN we trace the parts of which this terrestrial system is composed, and when we view the general connection of those several parts, the whole presents a machine of a peculiar construction by which it is adapted to a certain end. We perceive a fabric, erected in wisdom, to obtain a purpose worthy of the power that is apparent in the production of it. (Theory of the Earth, 2)

To say that time is ‘adapted to a certain end’ is not to assert an eschatological vision of time. It is to say that the movement of time itself is meaningful, which is not reducible to waiting for its divine end.

This, along with time’s elongation, is the foundational change to the human condition that the Enlightenment brings about through geology: time is no longer bookended by Genesis and Apocalypse with punctuated moments that signal God’s announcement of a new epoch. Time is the result of processes in motion whose progression can be deciphered in the landscape, as Hutton writes:

Great things are not understood without the analyzing of many operations, and the combination of time with many events happening in succession. (156)

This composition of time has no inherent need for a beginning or an end. Those questions, from the geologist’s perspective, can be held in abeyance.

But we also see a new composition of time that is inseparable from words such as combination, succession, events. Time, in other words, is beginning to be understood as the result of the causal movement of nature’s ‘many operations’.

The human condition is now firmly situated in a world composed of natural processes. God’s presence is tenuous at best, which leaves open crucial questions: Are those processes conducive to human flourishing? Are they indifferent or even hostile? Modernity will take up these challenges, but it was the role of the Enlightenment to set the problems in motion.