The Cave Paintings of Tito Bustillo

Can We Experience 17,000 Years?

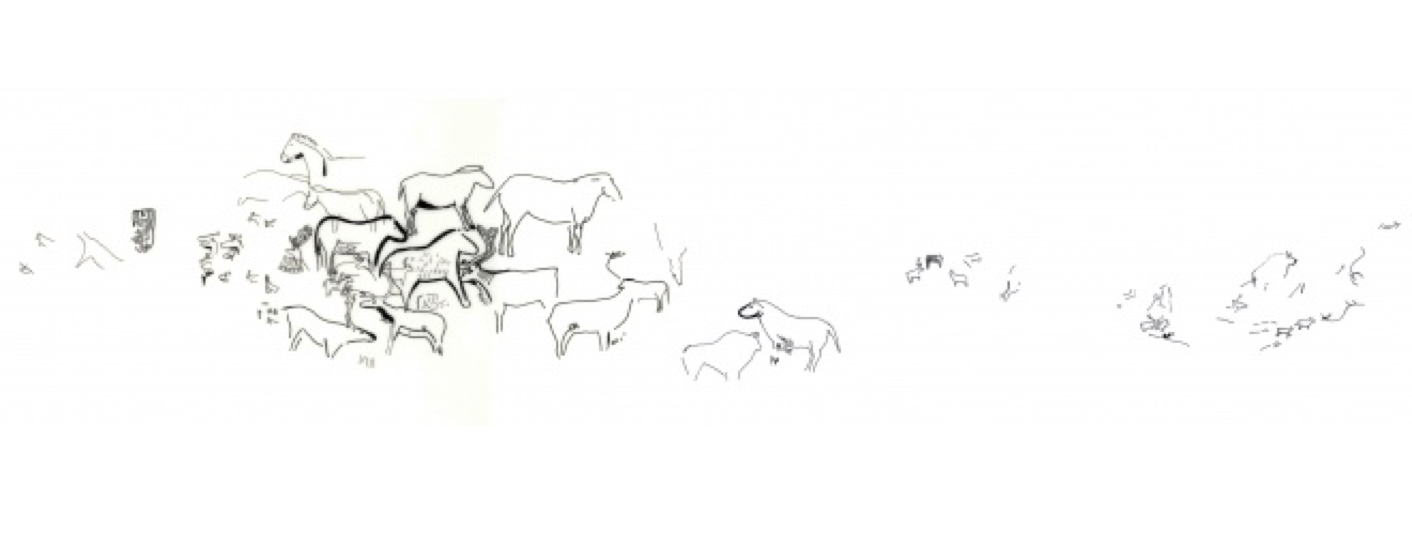

Part of Tito Bustillo’s Main Panel

I recently visited the caves of Tito Bustillo in Spain’s Asturias region. It is one of the few places where tourists can view the actual paintings made between seventeen to twelve thousand years ago, the Magdalenian period, which is considered a Golden Age of prehistoric cave paintings.[1]

Standing before these paintings means facing time on a scale that is hard to grasp. Seventeen thousand years—can we really take that in? Homo sapiens does not arrive on evolution’s scene with an automatic understanding of how long time stretches behind us. Barely three centuries ago, Isaac Newton estimated that God’s creation was only 5,700 years old. Today, we measure the universe at about 14 billion years, and the Earth at 4.5 billion. [2]

Perhaps this elongation of time is the most profound change in human self-understanding since the Enlightenment.

I know before entering the caves that I will see the work of Homo sapiens, but between us there are profound differences that I can only intuit. Those differences are chronologically tiny compared to the first Homo sapiens, which paleoanthropologists date to somewhere between 150,000 and 200,000 years ago.

The Neolithic Age has come and gone between us and the artists of Tito Bustillo.

Cave paintings unsettle Modernity’s trusted categories—nature, culture, religion, art, science—each long parceled into its own academic discipline. These categories collapse at Tito Bustillo, even as the tour moves with the linear clarity of Descartes’s cogito. In this essay, I don’t want to romanticize my experience, but rather test whether Modernity’s clear signals are beginning to dissolve again into noise.

Descartes’s cogito as shadow puppet: a tour guide explains one of the paintings. Source: https://www.centrotitobustillo.com/en/videos

Flashlights

Our guide carries the only flashlight allowed in the cave. I would like to use my iPhone to help the elderly man struggling over the muddy, rough, and dimly lit ground. Sometimes I do so when the guide isn’t looking.

Low path lighting provides minimal but steady illumination. Along the way, I see scientists—perhaps grad students on research grants—tucked away in nooks. With the steady light of their headlamps, they see clearly the objects they are studying.

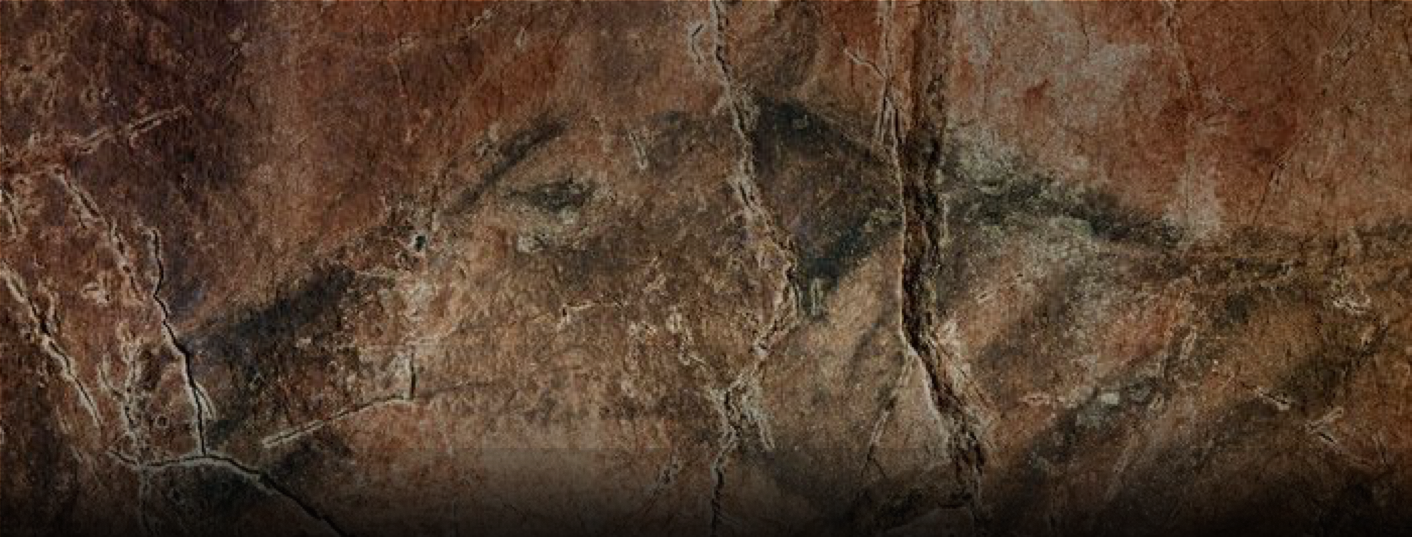

We arrive at the ‘Main Panel’—bison, horses, red deer, and reindeer. Some are painted on bulges in the rock face to provide a three-dimensional image. Like the vast majority of Paleolithic paintings, no humans are depicted.

The guide shines her flashlight on a magnificent black horse as she delivers her lecture—in Spanish, far too rapid for me to keep up with. The flashlight is steady, and the horse appears as an exquisite creature.

As the flashlight illuminates the drawings, I realize that I am having a thoroughly Modern experience incomparable to the inhabitants of the cave thousands of years ago. I immediately and viscerally realize that humans had harnessed fire by this time—no need for a textbook or a podcast to tell me so.

The flashlight hides as much as it reveals. It transforms the image into an object to be explained, analyzed, dissected.

This could not have been the painters’ experience. Whatever they saw by flames is gone from reach. I’m too far downstream to follow it back.

Is it possible to move upstream, even briefly, without drifting into nostalgia or Romaniticism or mysticism?

Explanations

Modernity sees the world as something to be explained. To know is to issue proofs—to strip language of metaphor and land at emotionless truth. Descartes’ natural light of reason became the model for all legitimate knowledge.

We’ve gained enormously from scientific clarity—our medicines work, our buildings rarely fall down. But in the process, art, literature, music, religion have been treated as lesser forms of knowing.

Modernity’s quest for certainty shepherds me through Tito Bustillo. We are on the clock—timed entry and fixed duration for the tour. The cave is a curated object, its paintings treated as religion or art, while the flashlight and the lecture wrap the experience in Modernity’s rationality.

Source: https://www.centrotitobustillo.com/en/el-arte-rupestre-de-la-cueva-de-tito-bustillo

Seeing the Place

St. Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises teach a method he called composition by seeing the place: imagining yourself inside the scene before searching for meaning—standing in the crowd at the Sermon on the Mount, sitting in the boat as Jesus approaches across the water, watching as he knocks over tables in the Temple.

It is a discipline of presence, of seeing ‘as if I were there’, before the machinery of interpretation goes to work. The task is not to decode but to let the scene appear in its own light.

Italo Calvino borrowed Ignatius’s technique as a way to engage myths first as literal stories. For Calvino, the literal is not opposed to the spiritual; it is what keeps experience from ‘escaping into dreams or into the irrational’. [3]

To see the place is to postpone explanation. We start simply by imagining ourselves inside the scene, present at the moment before meaning shines a different light on it.

In the caves of Tito Bustillo, the literal showed up for me involuntarily, and it collapsed space and time in an instant. Looking around at the lighting and passing through some pitch dark passages, I realize viscerally and suddenly: humans had already harnessed fire. No one could function in this cave without it.

I am experiencing this by electrical light and a battery powered flashlight. I am a tourist with a timed ticket. I am a sightseer with the help of these modern instruments.

Though I stand where the painters once worked, we do not see the same world. Vision is historically conditioned.

I resist reducing this to cultural difference. ‘Culture’ is a Modern category—meant to equalize all peoples as having cultures while turning them into objects of explanation.

On a map, we are in the same cave. Sightseeing, I am far downstream. What I see passes through artificial light, academic frameworks, and the instruments of Modernity—from Descartes’ rationalism to Edison’s electricity. Modernity uses these instruments to compose time as progress, always distancing the present from its so-called primitive past.

Recording and analysis of the rock art have been benefited of modern techniques of lighting, digital photography and, in some cases, 3D scanning. Graphic expressions have been also subject to direct chronometric dating and pigment analyses. [4]

I ask again: is it possible to move upstream from our downstream experience?

Source: https://www.centrotitobustillo.com/en/panel-principal

Moving Upstream

After returning home, a friend asks if I’ve ever read Georges Bataille. We share an interest in William James’s radical empiricism, and Bataille seems an obvious fit.

Though I was steeped in poststructuralism in the 1990s, I never read him. Foucault, Derrida, and others drew deeply from his idea of ‘transgressive experience,’ but I never followed the thread.

I decide to read The Cradle of Humanity, a collection of Bataille’s essays and lectures on the Paleolithic cave paintings, Lascaux in particular. In one of the essays, Bataille speculates:

Now let’s imagine before the hunt, on which life and death will depend, the ritual: an attentively executed drawing, extraordinarily true to life, though seen in the flickering light of the lamps, completed in a short time, the ritual, the drawing that provokes the apparition of the bison. [5]

Reading Bataille means attuning to motion. The apparition isn’t a static image but an emergence, a figure appearing through flickering light—not the dissecting precision of a flashlight. He does not explain the ritual; he tries to move into it, traveling upstream through Modernity’s insistence on clarity, toward an experience that can’t be reduced to aesthetic contemplation in the stillness of a museum.

This movement upstream isn’t nostalgia or a search for authenticity. Bataille knew it was an ‘impossible identification,’ yet one necessary for a postwar moral compass reorienting for the nuclear age.

Was the painter—priest, shaman, hunter—enacting a ritual for those about to kill? To treat these walls as finished art is to fix in time what was once alive, communal, and trembling in firelight. [6]

Even on a sightseer’s tour, a trace of that motion survives. When the flashlight’s beam drifts across the wall looking for the image, the light performs its own small ritual, and the drawing once again becomes apparition.

Modernity’s clear vision hesitates in that moment, and I am moved upstream.

Downstream Re-Entry

To look that far upstream—seventeen millennia—means confronting a scale of time that has only recently forced itself upon us. Up to and through the Enlightenment, calculating the beginning of time was an act of Christian exegesis: if read closely enough, the Bible would reveal the age of God’s creation.

The Earth, however, was revealing a much longer timeline. Enlightenment geologists, working ‘between 1750 and 1850, created a new and vastly extended time-scale, anchored in the rock strata and fossils of the Earth’s crust.’ [7]

Darwin and others in the nineteenth century stretched time backwards by giving us the blind and unpredictable process of ‘natural selection’. Earlier estimates seemed comical. We remember Newton’s laws of motion and his discovery of gravity. We forget his Biblical chronology of 5700 years. [8]

Everything changes when we stretch time out that far. Darwin himself contemplated the experience of vastly elongated time when he wrote of geology in his chapter ‘On the Lapse of Time’:

Therefore a man should examine for himself the great piles of superimposed strata, and watch the rivulets bringing down mud, and the waves wearing away the sea-cliffs, in order to comprehend something about the duration of past time, the monuments of which we see all around us. [9]

Back in the parking lot, I re-enter the downstream, which is saturated with computational control. Everywhere I look is an engineered landscape—roads, bridges, power lines, signs, buildings. I get back in my Hertz rental car that I paid for with my Chase credit card reserved months in advance with my Hertz.com account. I enter my next destination into the GPS, which I have set to speak English rather than Spanish, never seriously doubting that I will efficiently and predictably reach Bilbao around the time estimated on the screen.

Notes and Further Reading

1 For a brief description of the Main Panel paintings, which cover two phases—before 20,000 years ago and 17,000-12,000 years ago—see the Tito Bustillo visitor center site. Other paintings are over thirty thousand years old and include early anthropomorphic figures. besides its accessibility, Tito Bustillo is special because it covers s a broader span of time than any of the more famous sites.

2 In his Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended, Newton reconstructed ancient history using both Scripture and classical sources. Working backward through biblical genealogies and astronomical references, he placed the Creation at 3998 B.C.

3 Six Memos for the New Millennium, page 8. Geoffrey Brock trans. See also pages 103-6: ‘What I think sets Loyola’s procedure apart, even with respect to the forms of devotion of his own time, the shift from word to image as the path too understanding profound meanings.’

4 An excellent academic review of the caves of Tito Bustillo is Balbín-Behrmann, R. de, et al., The Palaeolithic art of Tito Bustillo cave (Asturias, Spain) in its archaeological context, Quaternary International (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.quaint.2016.01.076

5 Cradle of Humanity, page 51. Translated by Stuart and Michelle Kendal.

6 See Balbín-Behrmann, et al. for their discussion of the likely fluidity between religious ritual and daily living.

7 Stephen Toulmin and June Goodfield, The Discovery of Time, University of Chicago Press, 1965, page 141.

8 See Toulmin and Goodfield’s gloss on Newton’s other calculation, which he dismissed in favor of his Biblical math: ‘Newton had gone so far as to enquirer, in an incidental note, how long it would take for an iron sphere the size of the Earth to cool down from red heat…’ The answer was roughly 50,000 years. ‘For once, Newton’s calculations led to a result he could not square with religious convictions, and he unhesitatingly rejected it.’ (146-7).

9 The Origin of Species, Cambridge University Press, 2009, page 266.